It's a time of year for fresh starts – whether that's in the form of an inspiring resolution, or a cleansing scent to start (or end) the day.

The perfume world has long catered to those seeking freshness in their fragrance. Enter aldehydes: not a flower, a resin, or a wood, but a creation — molecules that mimic the crisp, airy scent of electric skies and sun-warmed linen. They belong less to the earth than to the atmosphere itself.

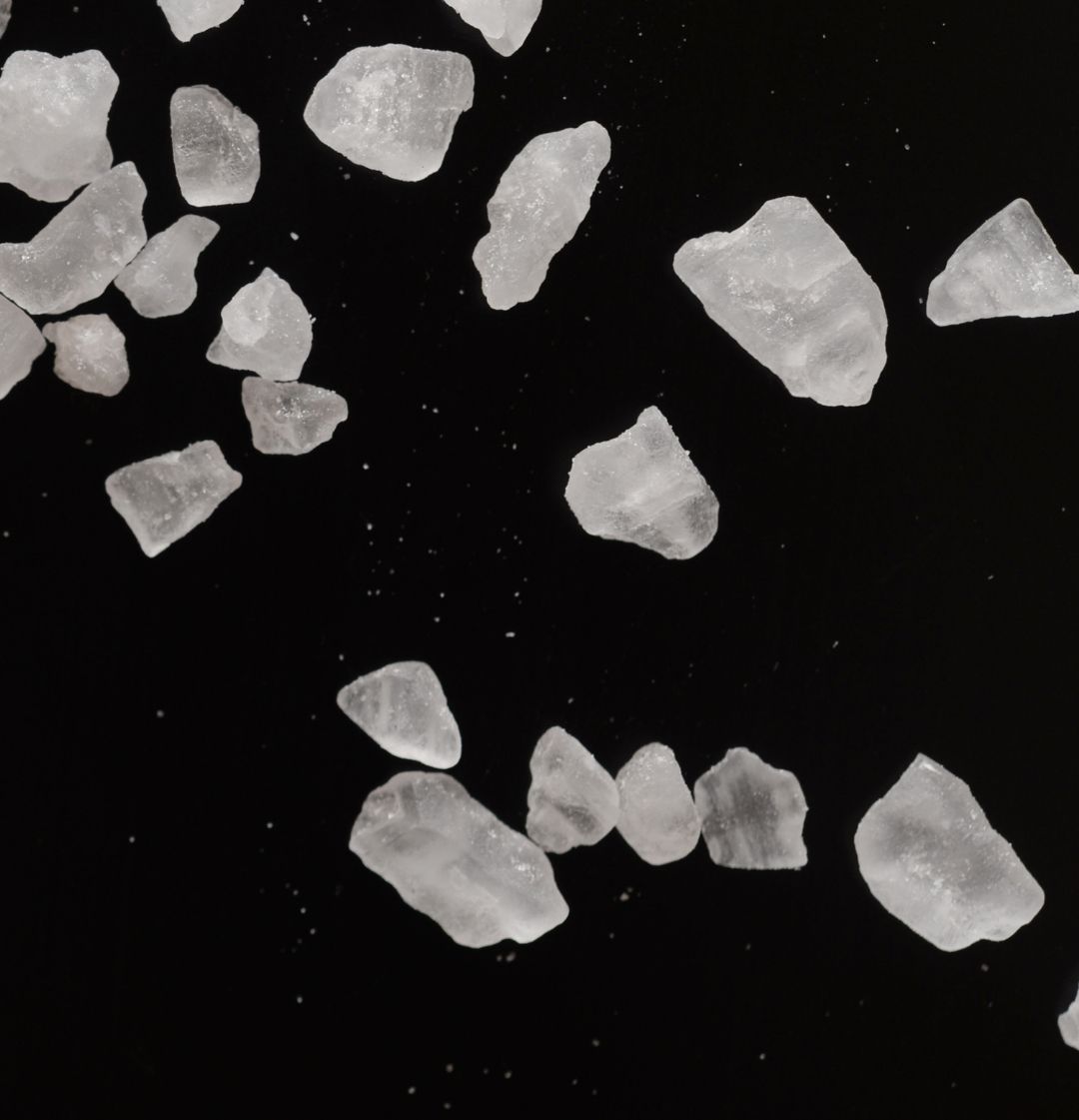

In chemical terms, aldehydes are organic compounds defined by a carbonyl group (C=O) bonded to at least one hydrogen atom, written as R–CHO. This structure gives them their volatility — their tendency to lift, to sparkle, to evaporate quickly. In perfumery, that volatility becomes sensation: brightness, diffusion, space.

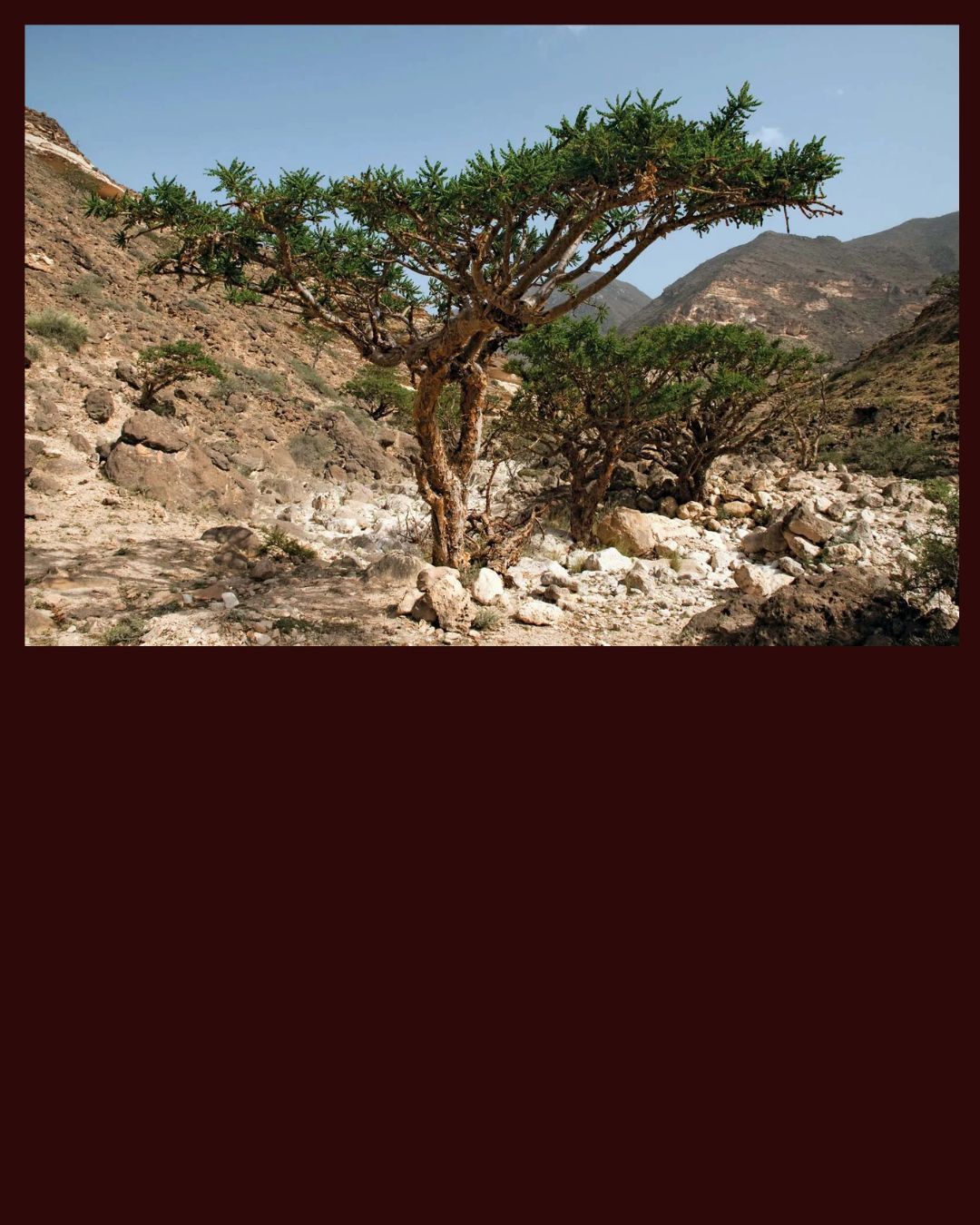

While aldehydes do exist naturally — in citrus peels, rose oil, coriander, cinnamon bark, and green materials — the aldehydes most associated with the “clean” and radiant effect in modern fragrance are synthetic aliphatic aldehydes. Created in laboratories for precision and consistency, they allowed perfumers to express something nature could not reliably provide: the feeling of air itself.

In the early 20th century, perfumers realised they could capture lightning in bottles. In 1921, Ernest Beaux’s use of high concentrations of synthetic aldehydes in Chanel No. 5 marked a turning point in fragrance history. Scent was no longer bound to literal imitation of flowers or woods; it could become abstract. It could evoke light, cleanliness, elevation, and distance — chemistry made poetry.

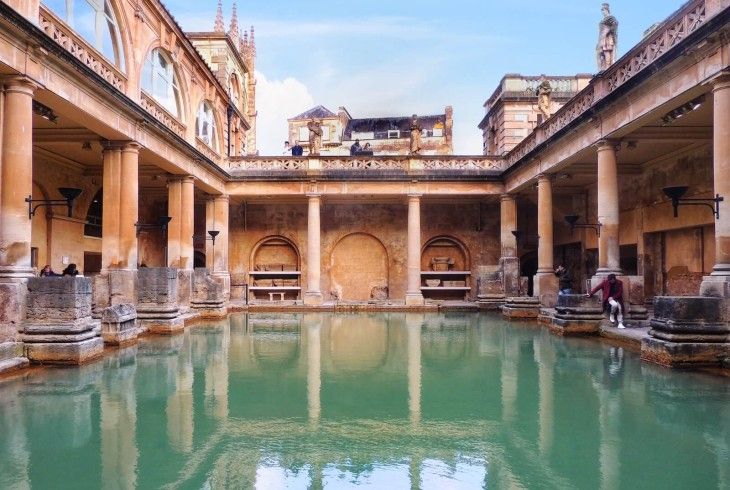

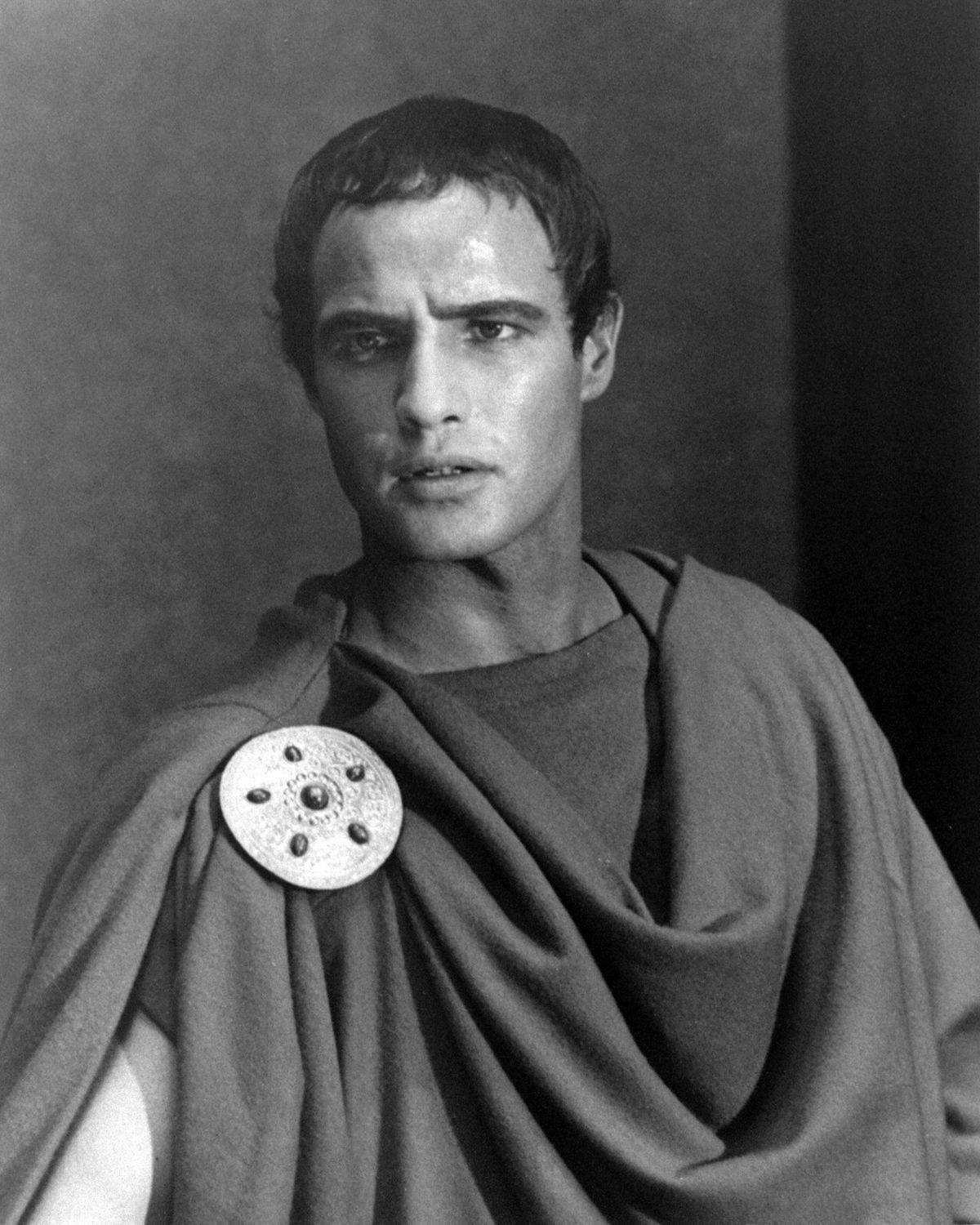

Think of stepping onto palace balconies at dawn, when morning air carries a peculiar clarity that makes distant mountains seem close enough to touch. Or opening shutters onto Alexandria’s harbour after rain has washed dust from stone streets. That crisp, almost metallic brightness that makes you inhale more deeply, as though you could store atmosphere itself in your lungs. Aldehydes gave perfumers the ability to bottle that otherworldly lift.

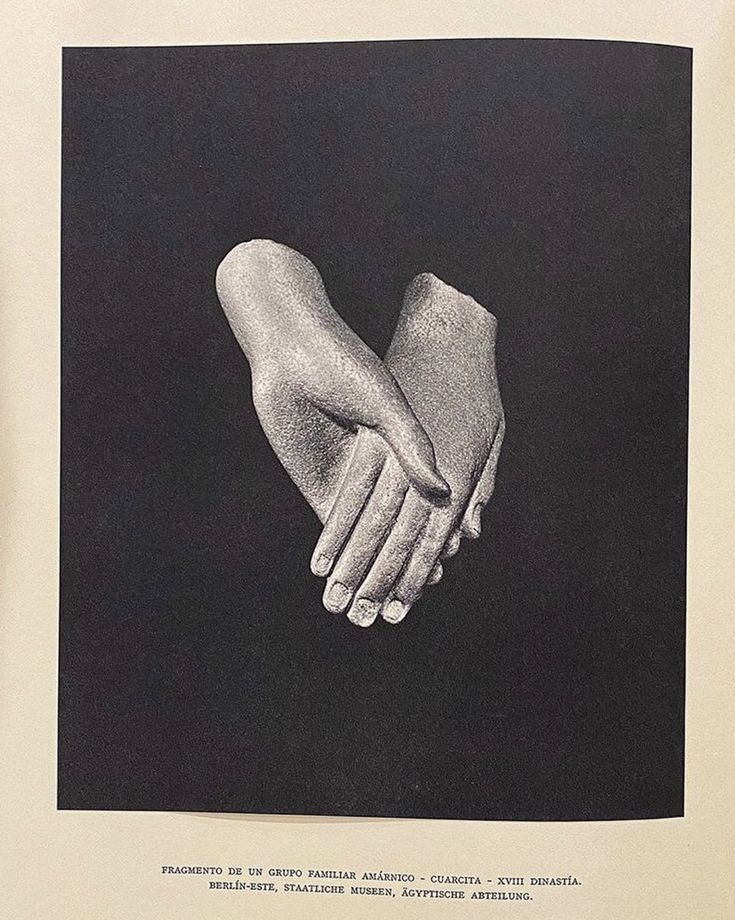

In a composition, aldehydes appear first. They evaporate quickly, which is why they are most noticeable in the opening of a fragrance. But they do not disappear without consequence. As they rise, they clarify everything around them — amplifying diffusion, extending structure, creating the illusion that scent exists not on the skin, but slightly above it. Never clinging, always floating. The olfactory equivalent of silk draped over the body.

Early perfumers understood aldehydes as tools of transformation — molecules that could make earthbound materials feel celestial, that could give weight to weightlessness, substance to sensations previously held only in memory.

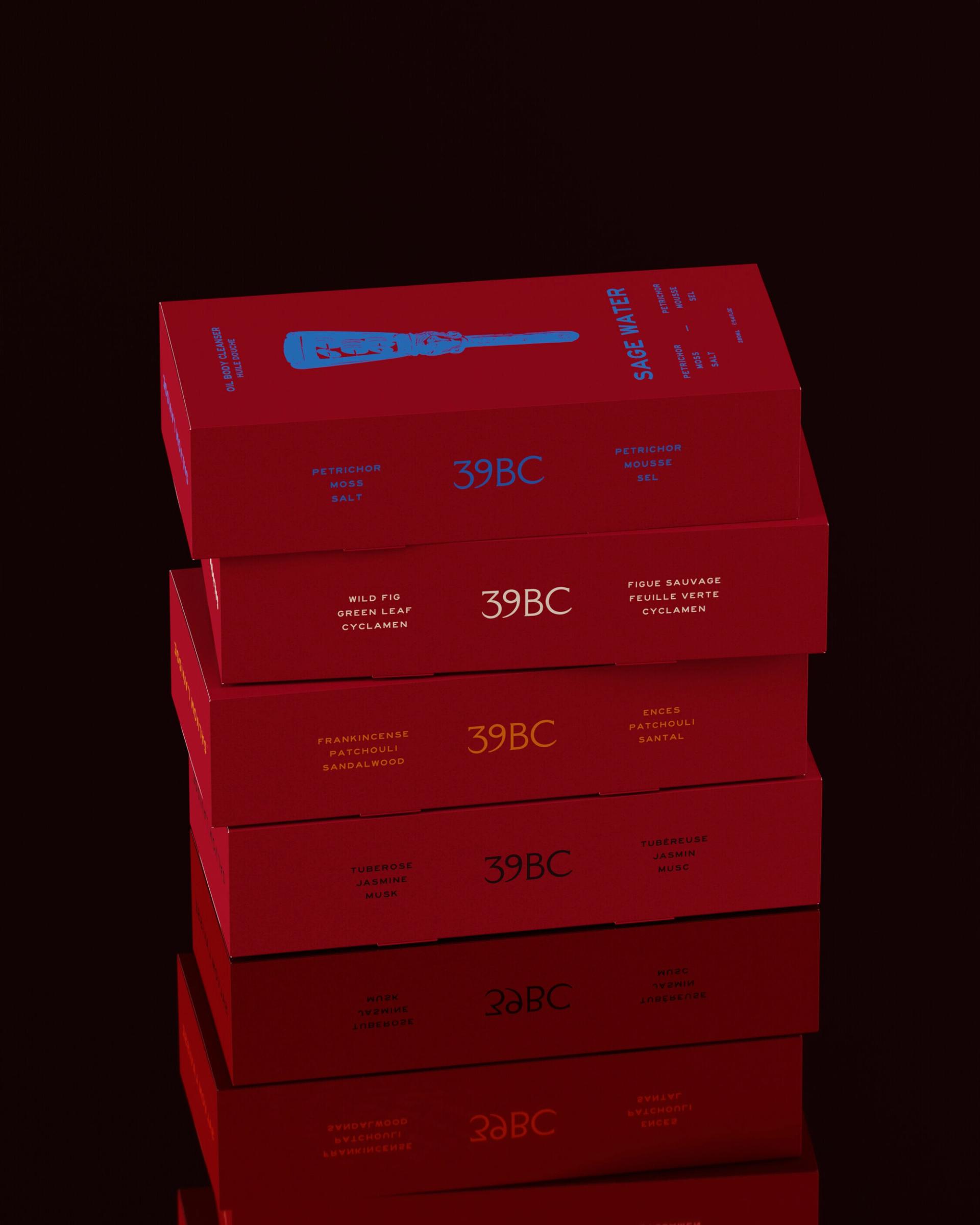

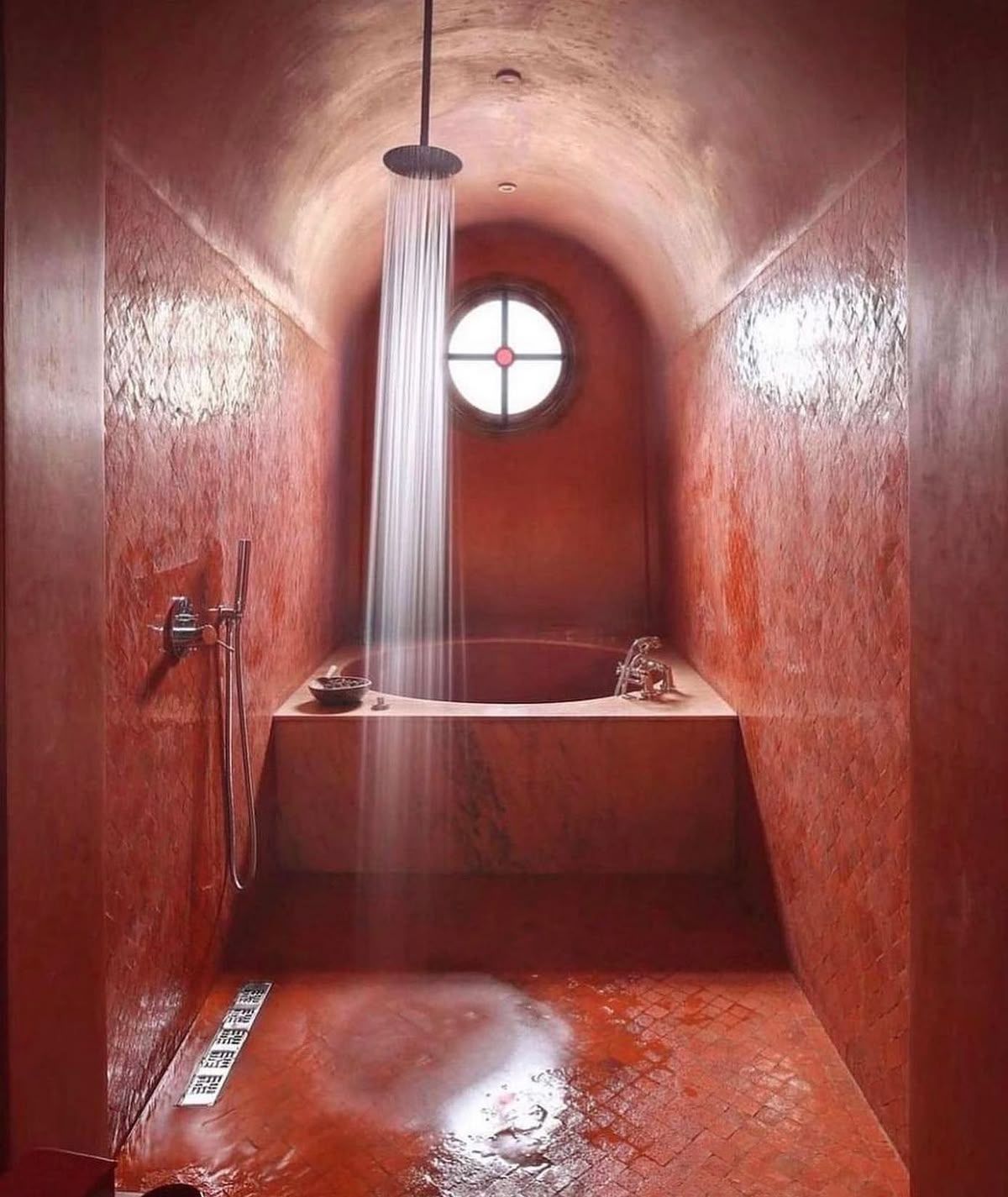

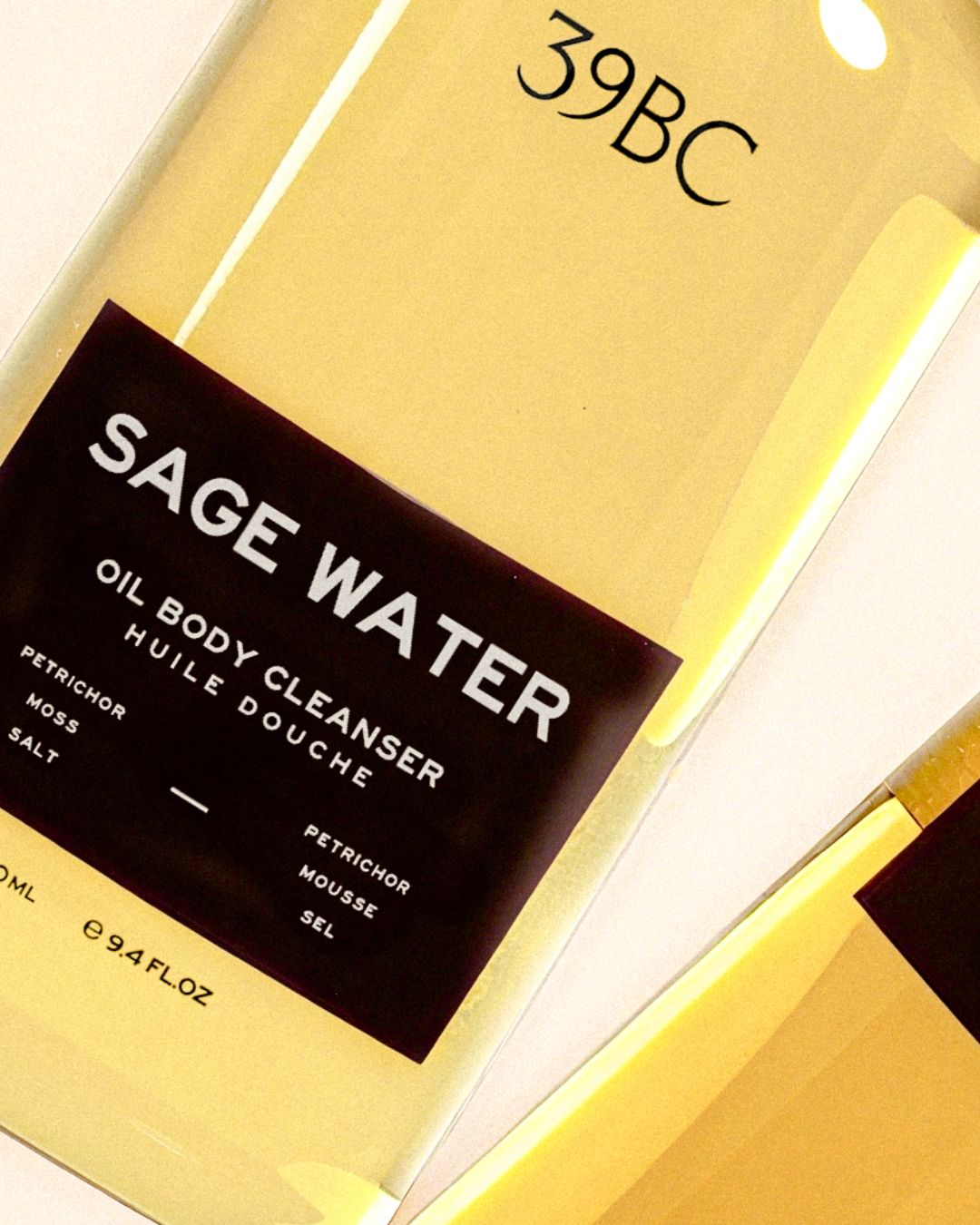

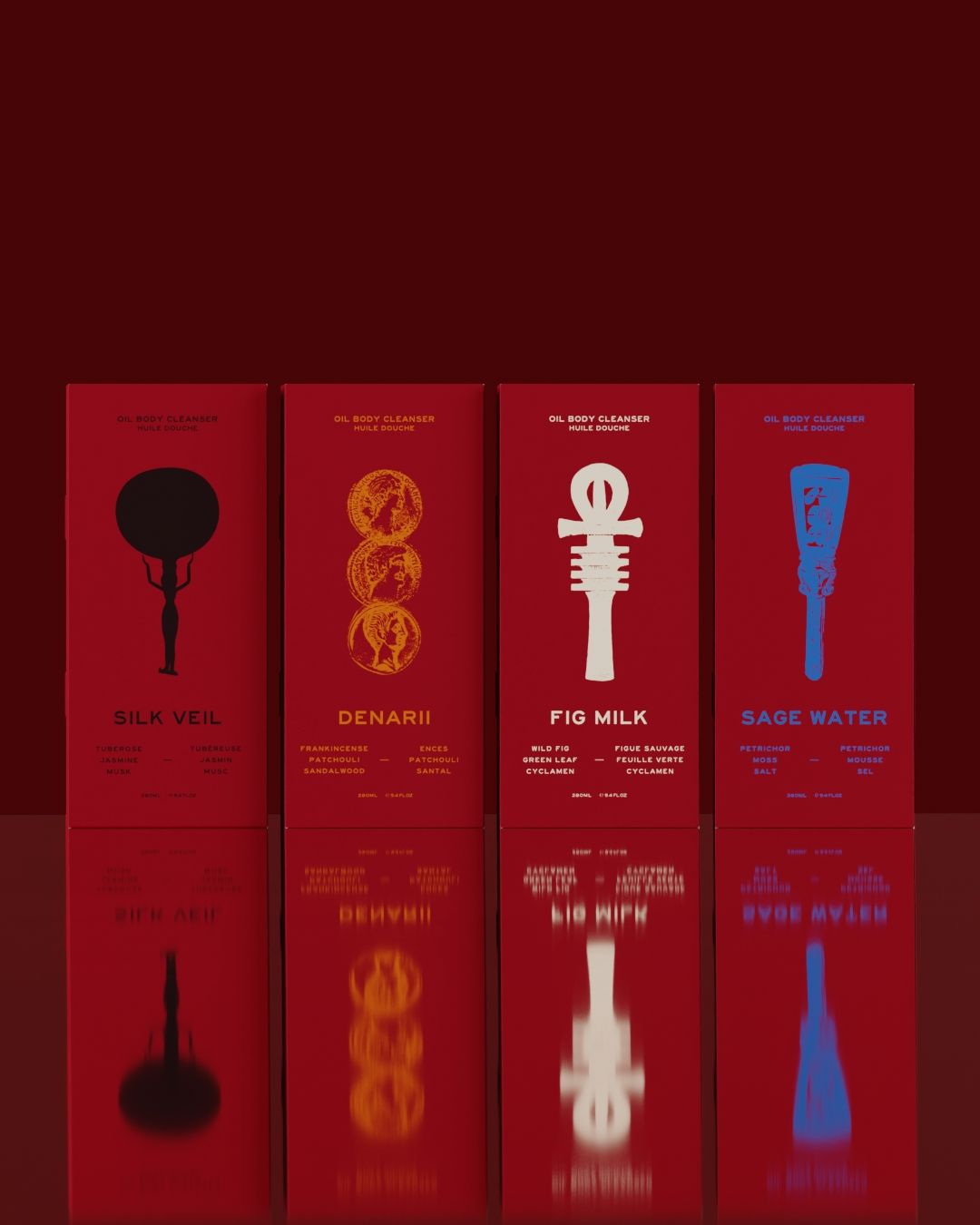

In SAGE WATER, aldehydic facets provide brightness, distance, and elevation. They introduce clarity without sterility, cleanliness without sharpness. They allow the deeper notes — wet earth, resin, mineral facets — to emerge slowly, without heaviness. It is not the scent of cleanliness itself, but the chemistry of clarity at work.

The cleanest note in the ceremony.