To the modern nose, patchouli might conjure images of long-haired hippies, daubing essential oils behind their ears. Its true history is far more powerful, complex, and dramatic.

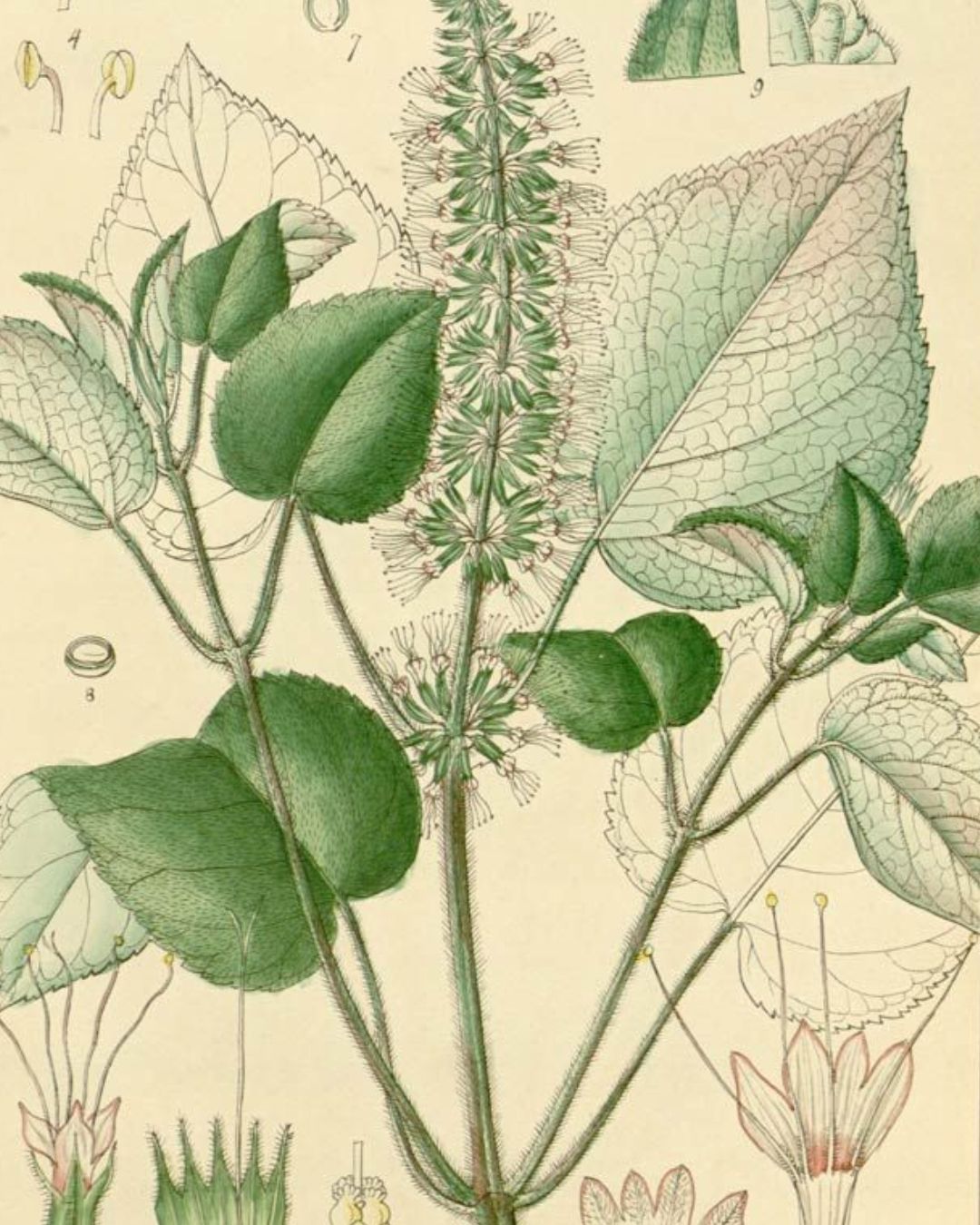

Patchouli begins as a leaf: dark, resinous, and aromatic. Native to the humid highlands of Southeast Asia, it flourishes in monsoon shadows. Its fragrance is unmistakable: damp earth, rain-soaked wood, the musk that lingers after storms.

Centuries ago, traders recognised its value. Chinese silks and Kashmiri shawls were layered with dried patchouli leaves, not for decoration but protection. The earthy aroma repelled insects that might destroy months of work, while perfuming the fabric so distinctly that European aristocrats learned to authenticate textiles by scent alone. By the time these silks reached Mediterranean markets, they carried not just colour and weave, but the smell of long journeys — jungles after rain, leather, soil baked by heat.

Patchouli’s role extended far beyond trade. In Tamil and Ayurvedic medicine it calmed restless minds, cooled fever, and steadied bodies unbalanced by exhaustion or desire. In Indonesia, priests burned it in temples, its smoke anchoring meditation, tethering spirit to flesh. And in China, courtesans pressed patchouli into silk sachets or onto their skin; warmed by the body, it released a subtle, sensual perfume, clinging to garments and sheets as a trace of intimacy.

At 39BC, this legacy is honoured in Denarii, a fine-fragrance shower oil. Here, patchouli lends depth and steadiness: grounding cedarwood, balancing raspberry, bridging into the creamy warmth of sandalwood. It is the weight beneath the pleasure, the earth beneath the fire.

Patchouli does not pass quickly through air. It settles. It stays. It becomes part of skin, fabric, memory. A scent that holds — grounding, enduring, unforgettable.

Because in every culture, patchouli was never merely perfume. It was ritual, medicine, seduction, protection. And in Denarii, it remains all of these: fragrance as anchor, presence as perfume.