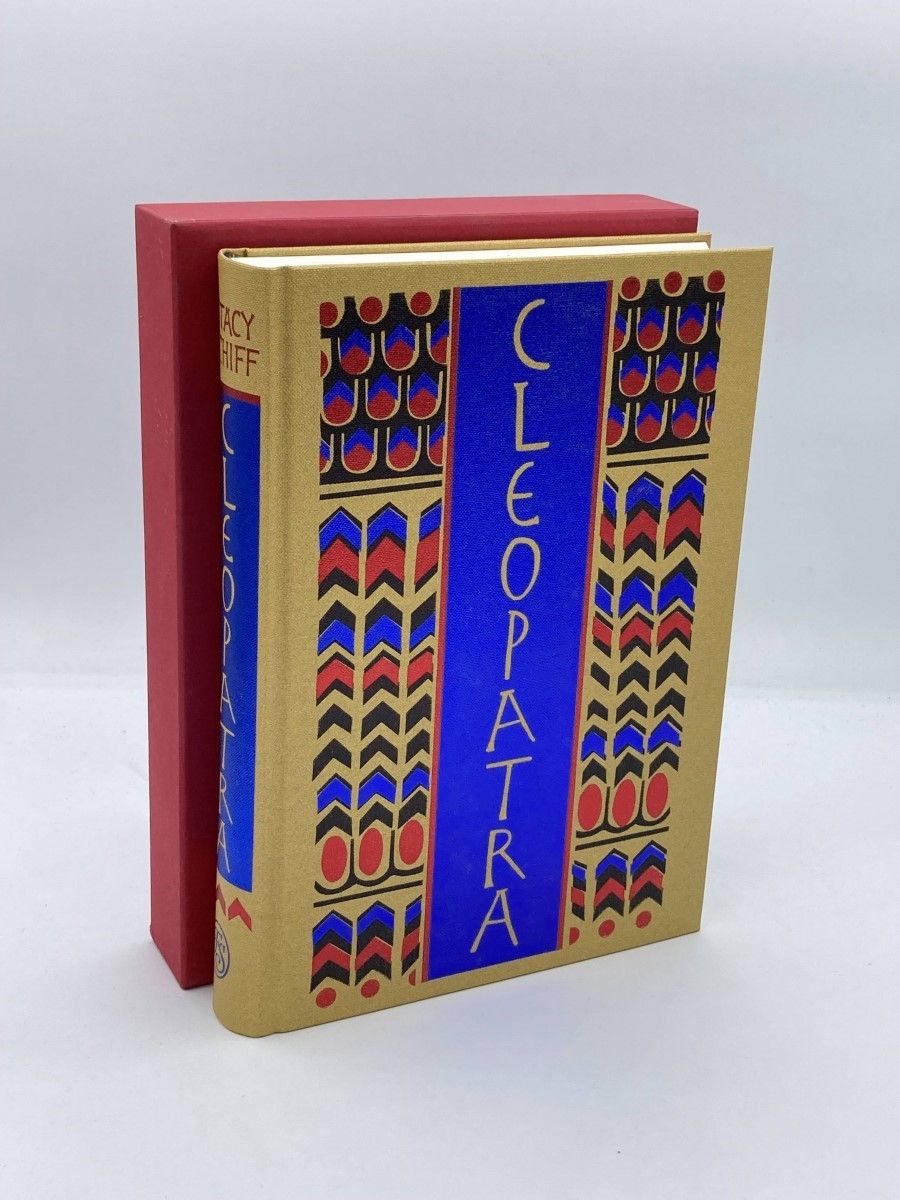

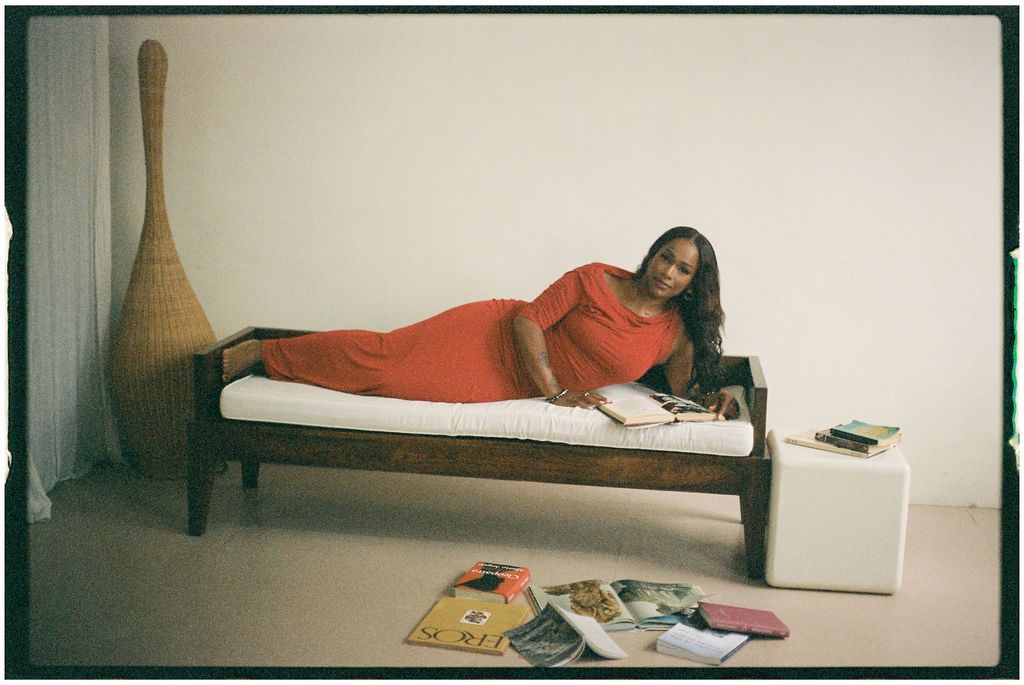

The fact that we know very little about Charmion - one of Cleopatra VII’s closest attendants - speaks volumes in itself. Here was a figure who lived in history’s margins, yet whose presence shaped its most charged moments.

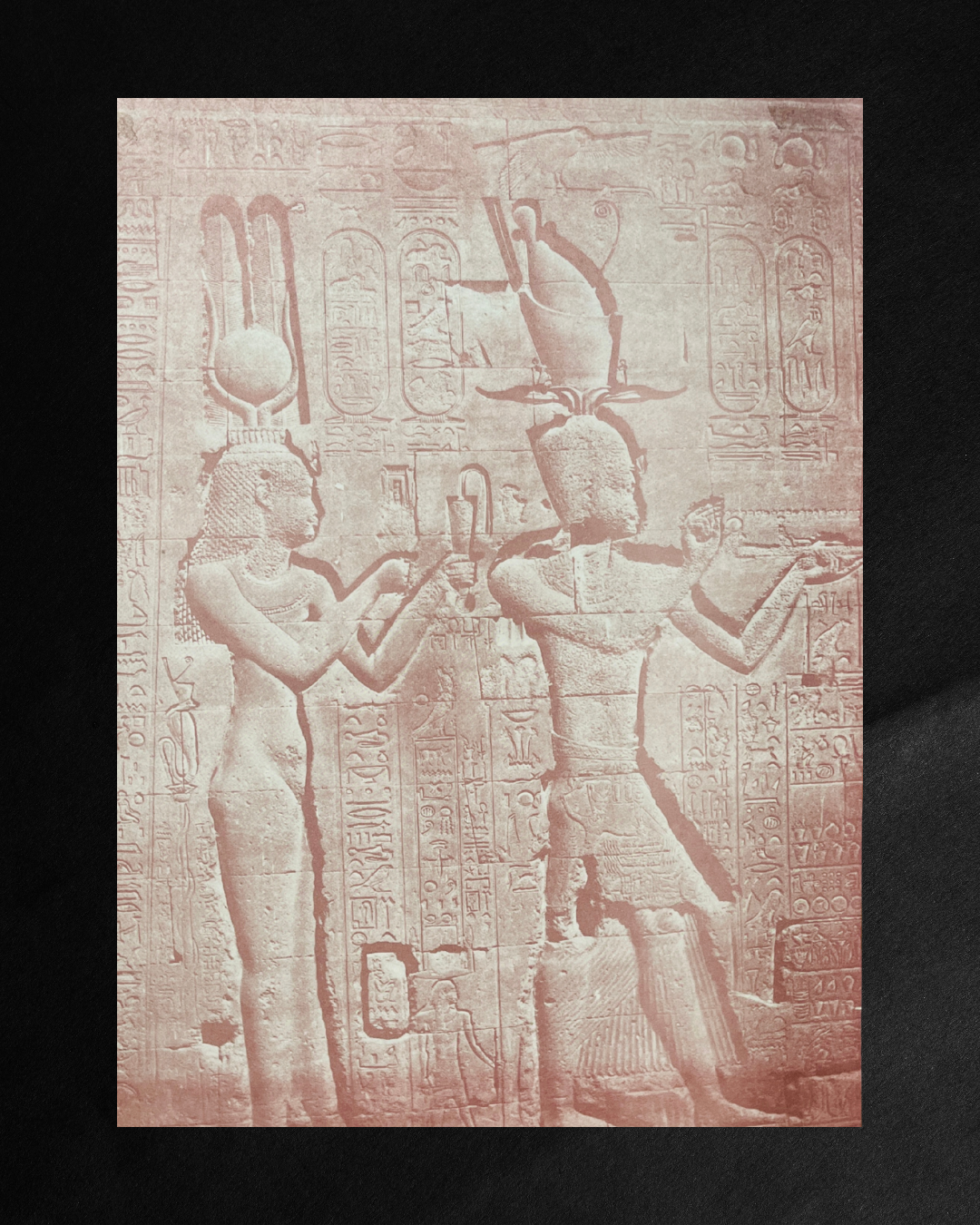

Almost nothing is recorded of her origins: no family, no birthplace, no path into the queen’s service. What survives is her role. She was a confidante and ritual specialist in a court where beauty and politics were indivisible, where private ceremony was inseparable from public power.

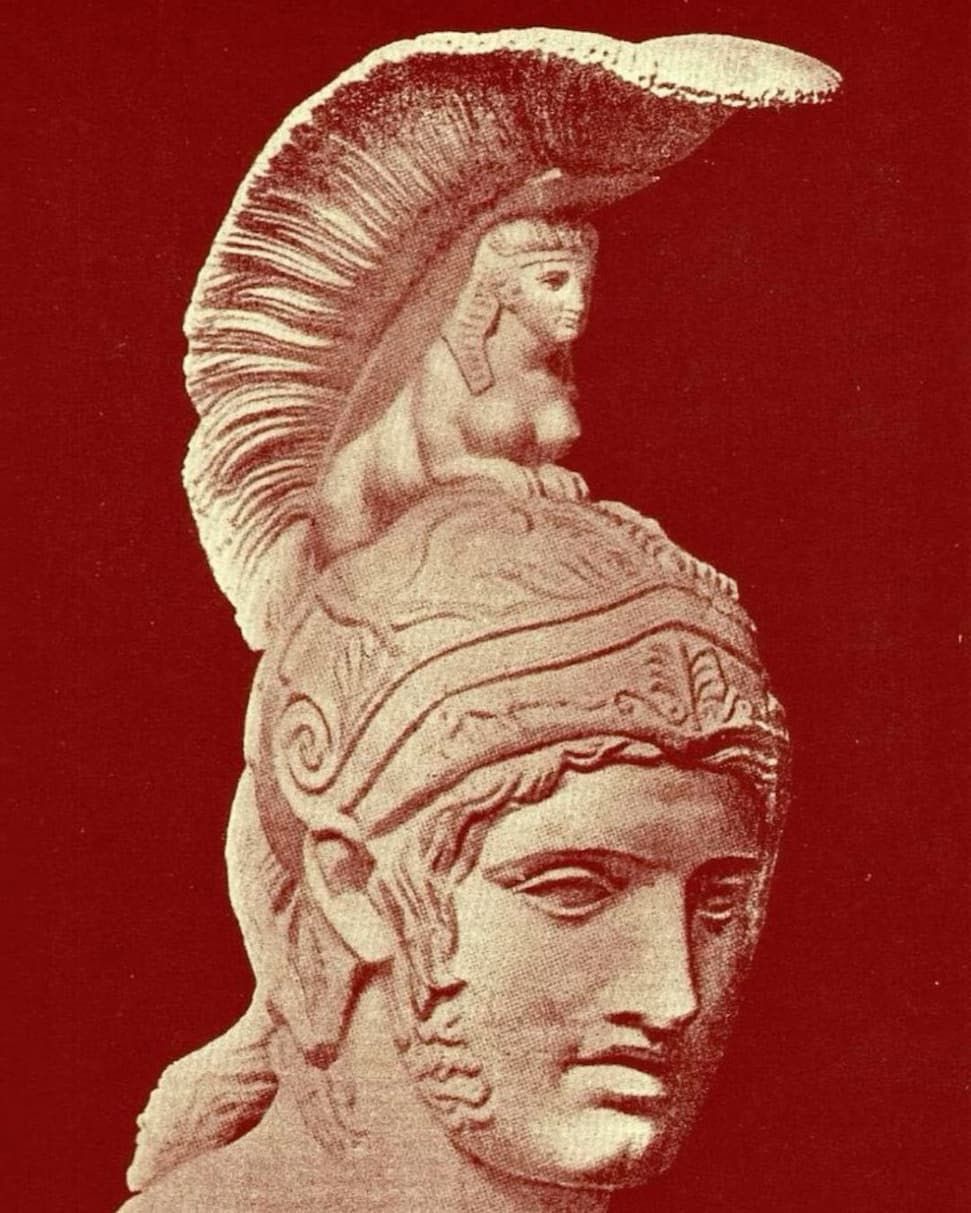

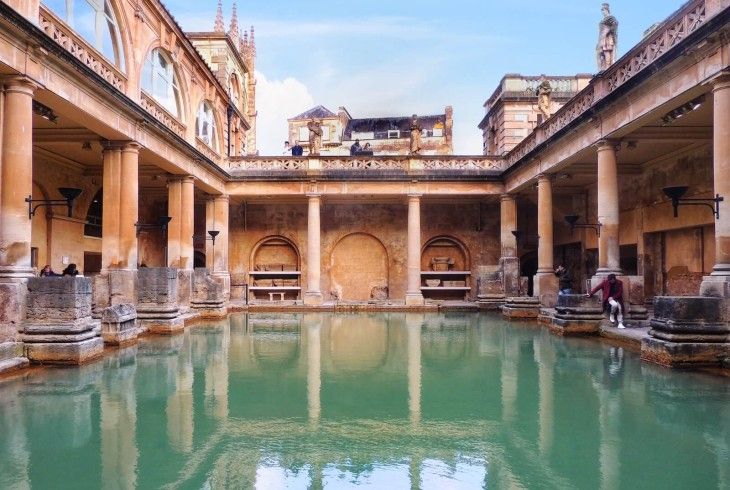

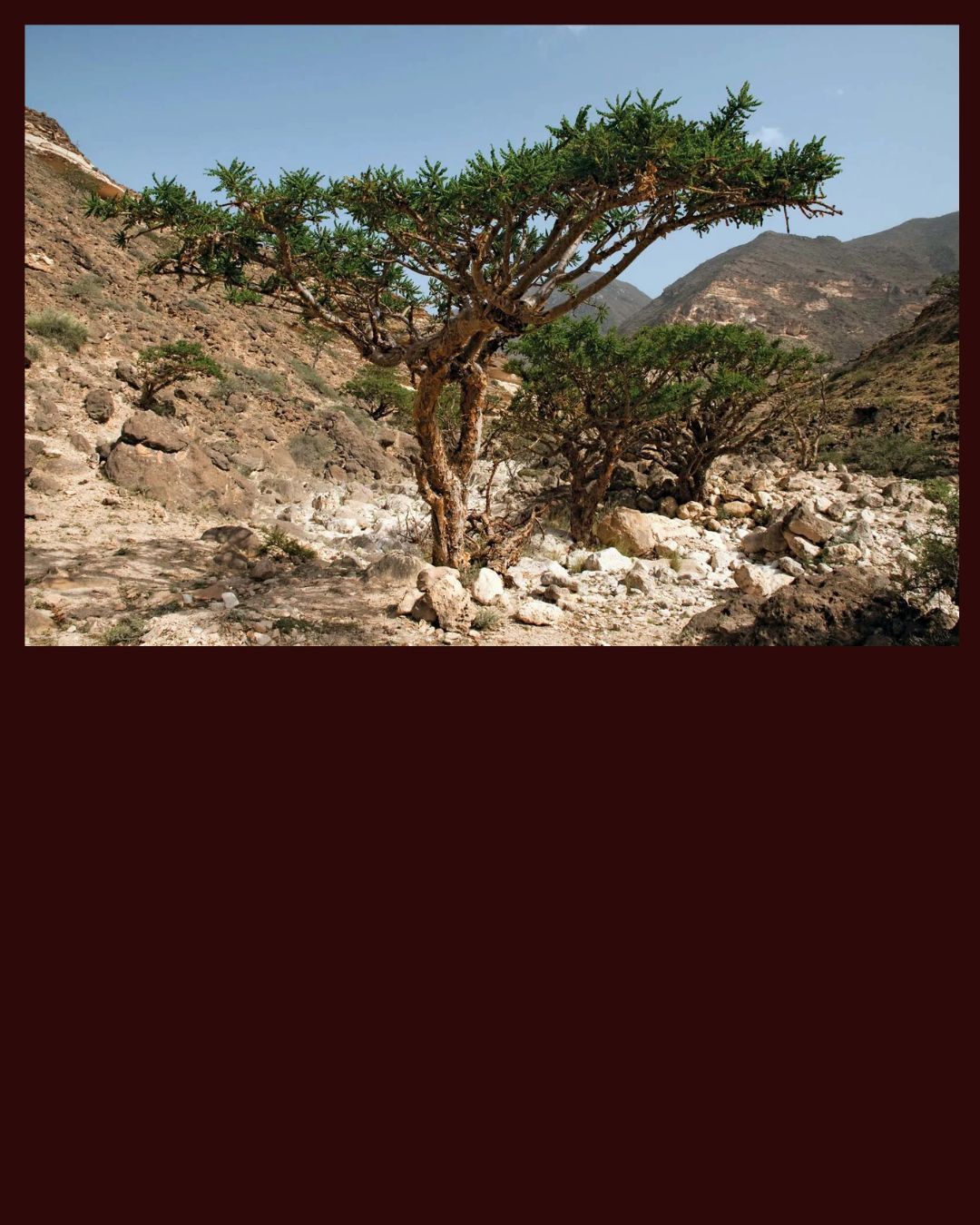

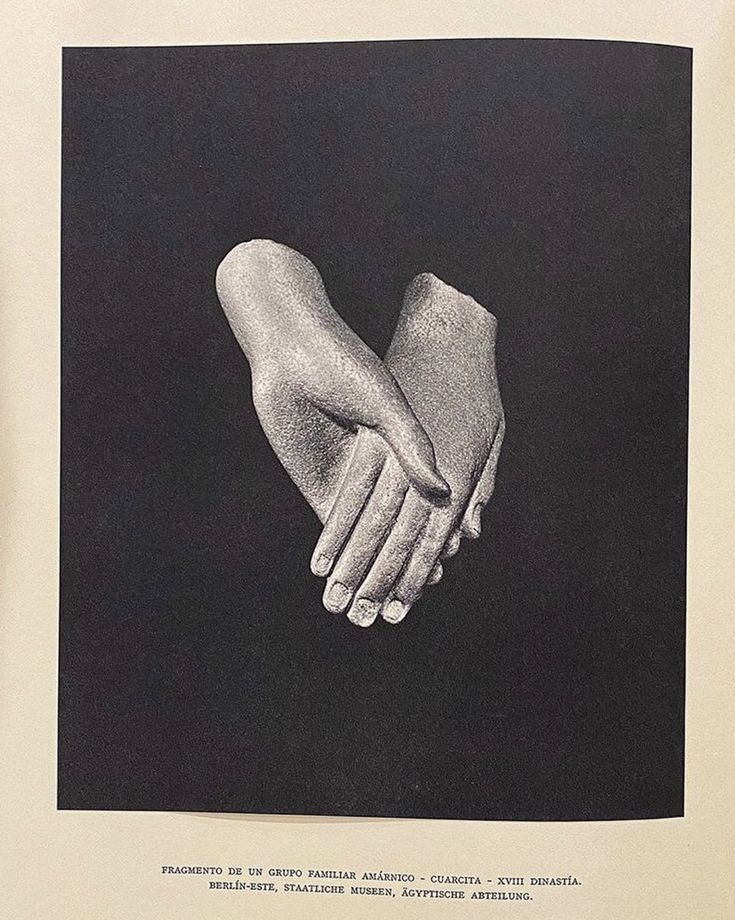

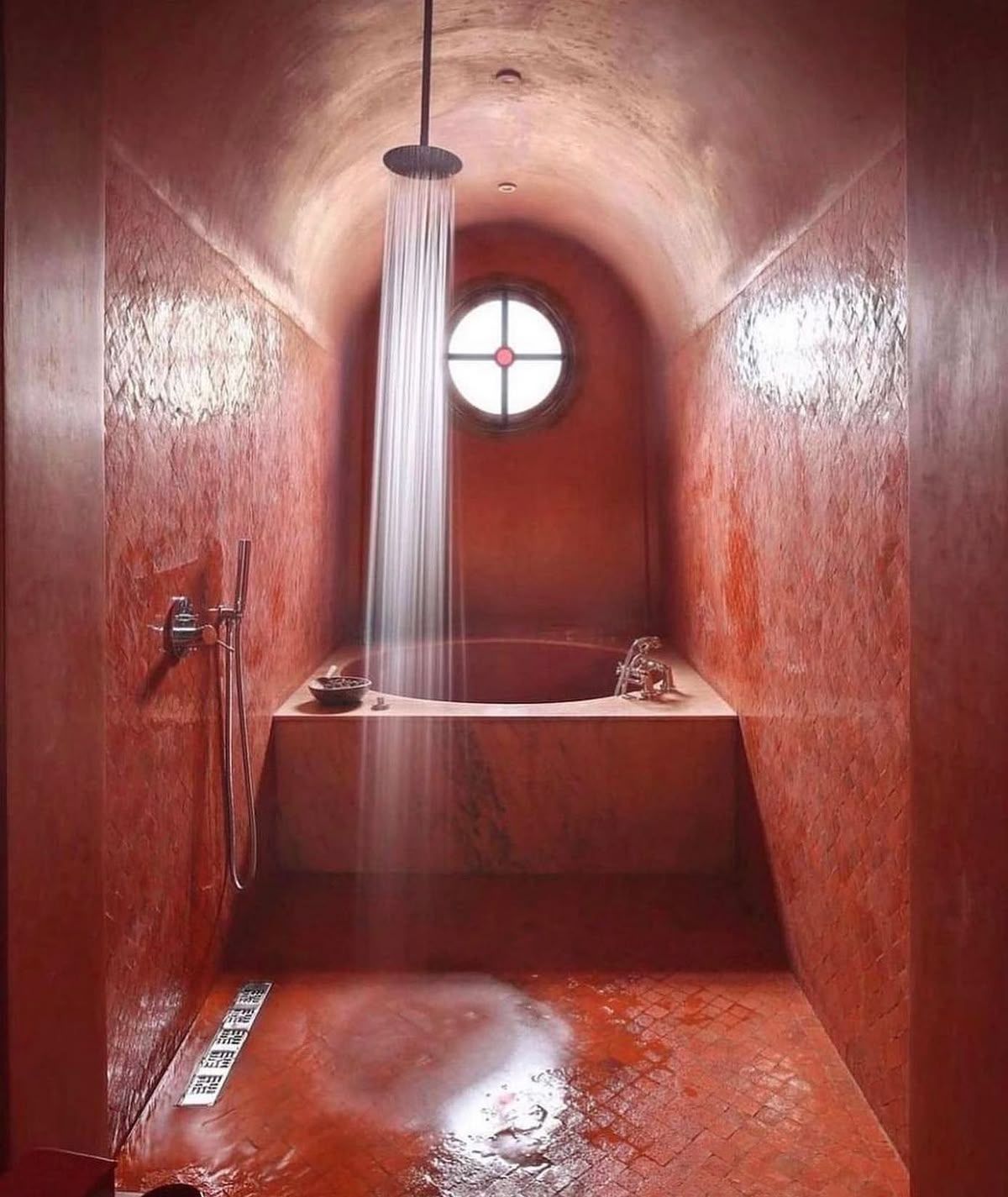

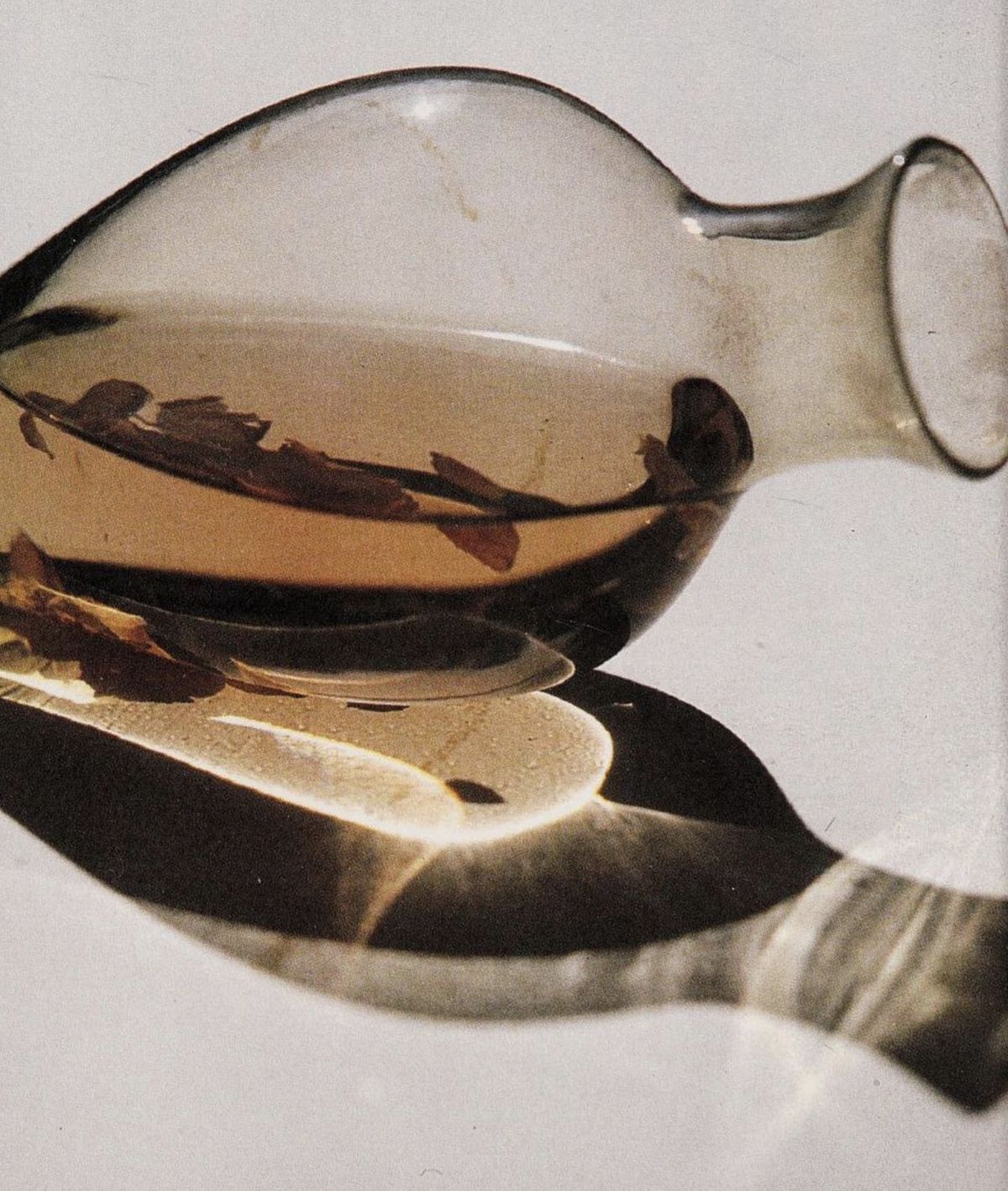

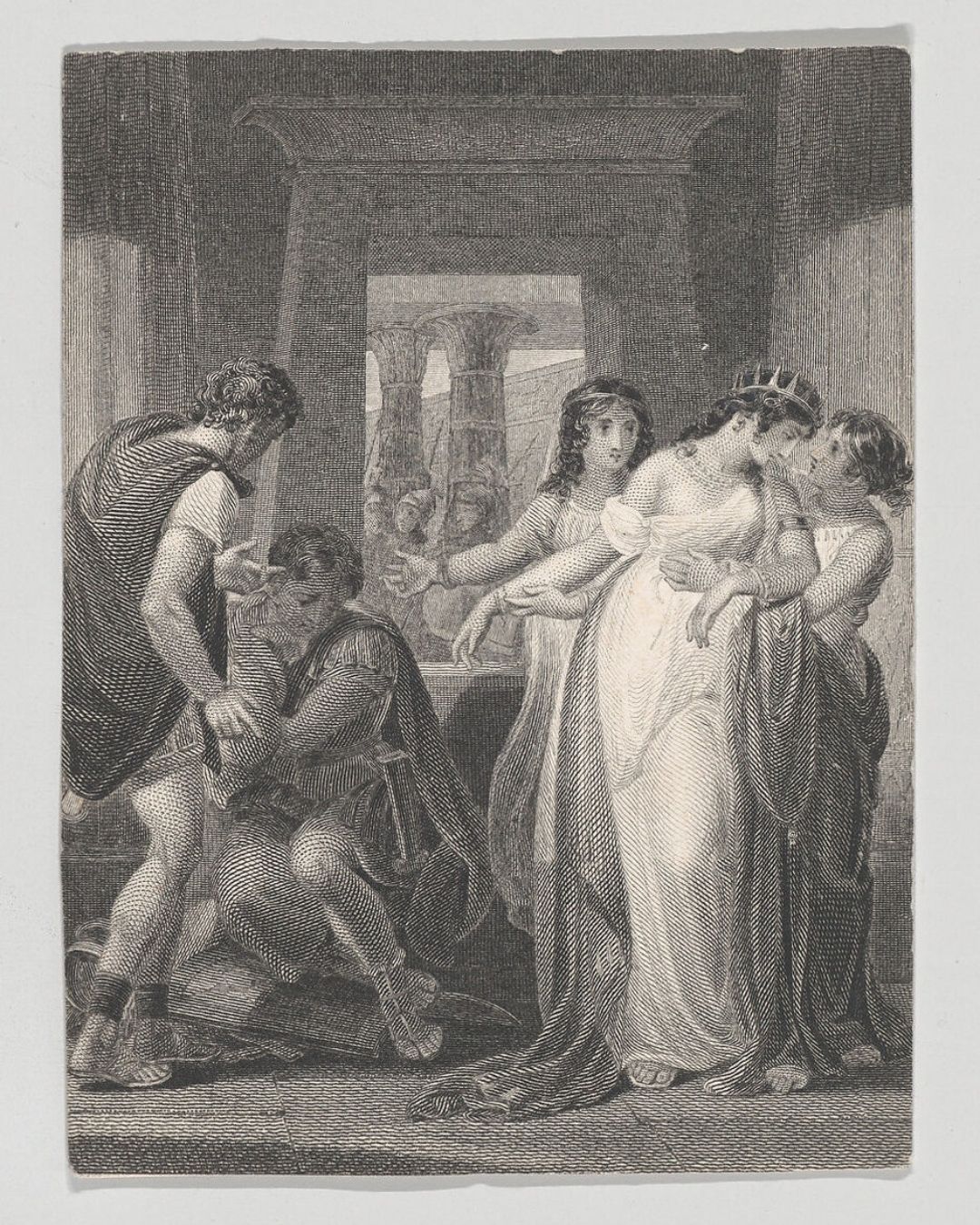

In Cleopatra’s chambers, Charmion would have prepared jasmine petals and alabaster vessels of milk, warmed oils in golden bowls, and adjusted diadems with ritual precision. Such gestures were transformational, turning a mortal queen into a living goddess before she stepped into the world outside. Handmaidens like Charmion were literate, entrusted with sacred texts, royal correspondence, and the secret formulas that shaped political theatre as much as personal presence.

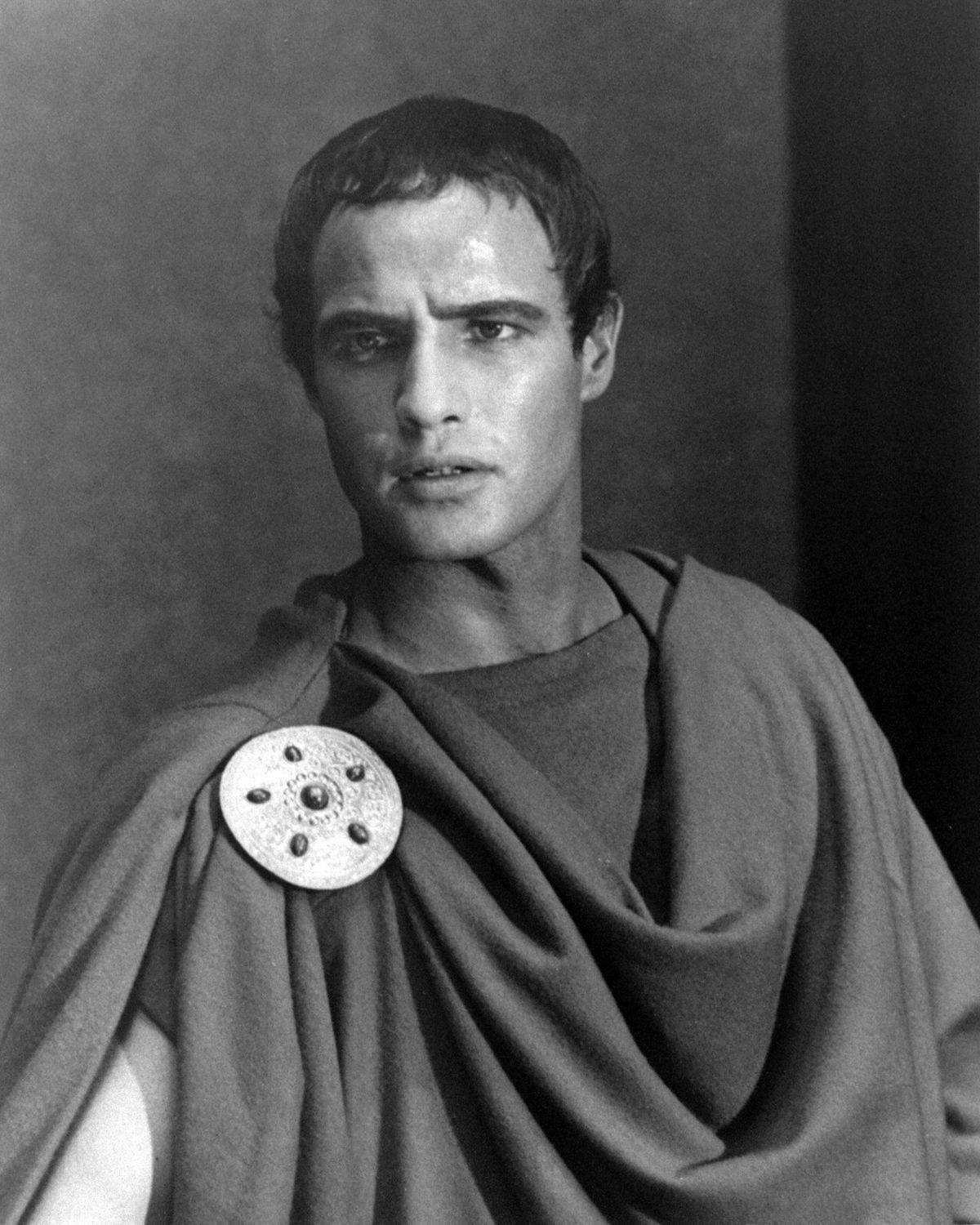

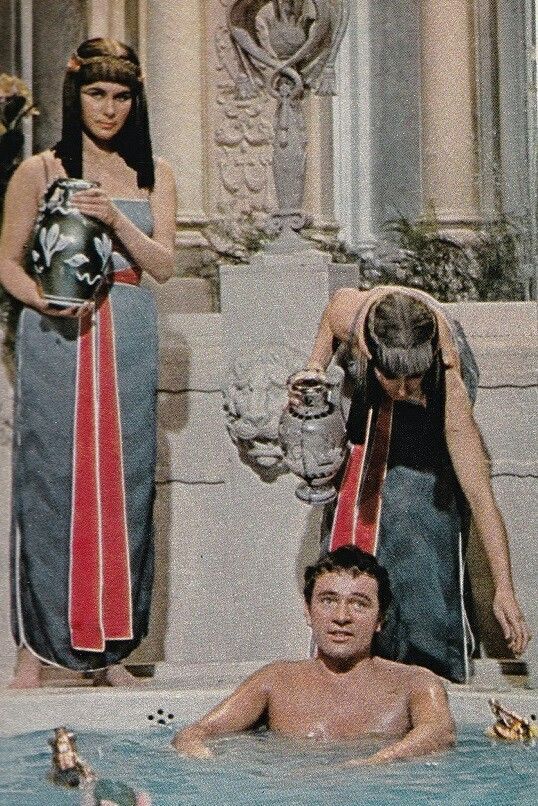

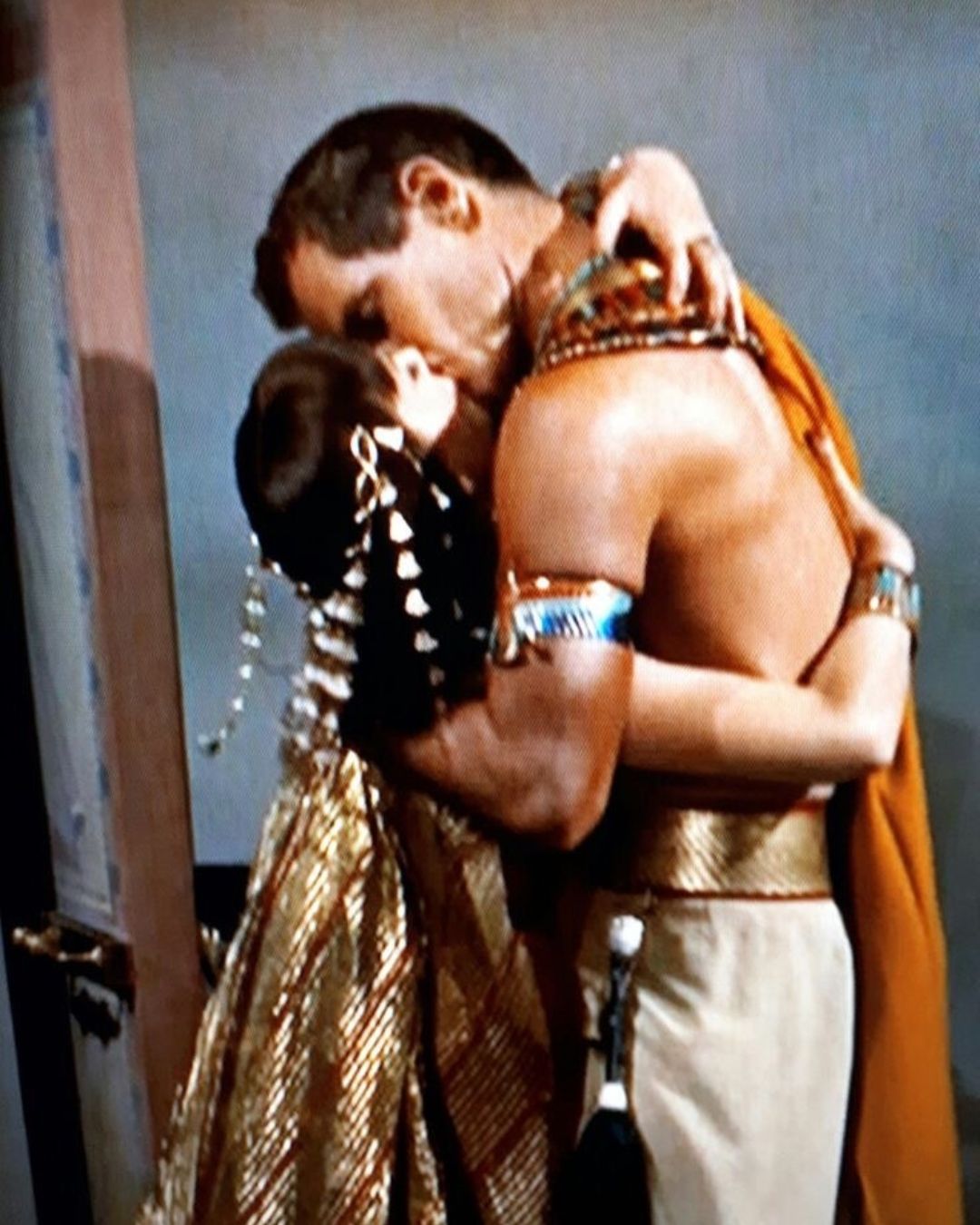

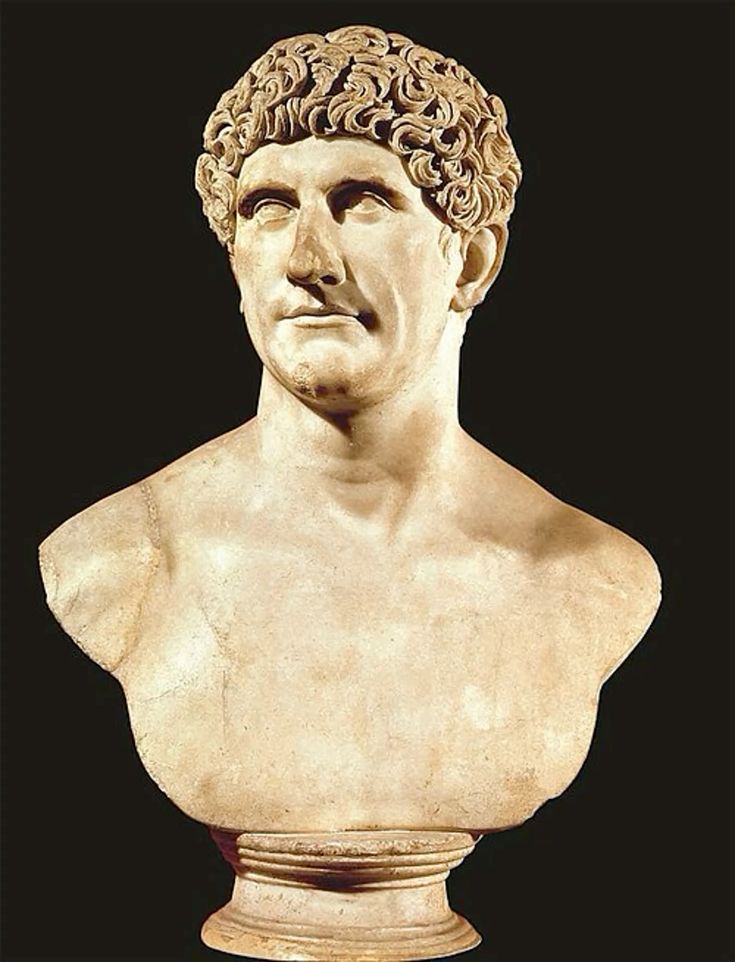

She witnessed confidences that could alter empires: letters to foreign rulers, whispered strategies with Antony, the moments when Cleopatra’s tears were genuine and when they were calculated. And she was there at the end. In 30 BCE, as Octavian’s soldiers broke into the mausoleum, Cleopatra lay on her golden couch, already claimed by the asp. Presentation remained paramount. Charmion adjusted her queen’s crown so Rome would see not ruin, but sovereignty. Confronted by soldiers, her final words were simple: “It is indeed fitting, for a descendant of so many kings.” Moments later, she joined her queen in death.

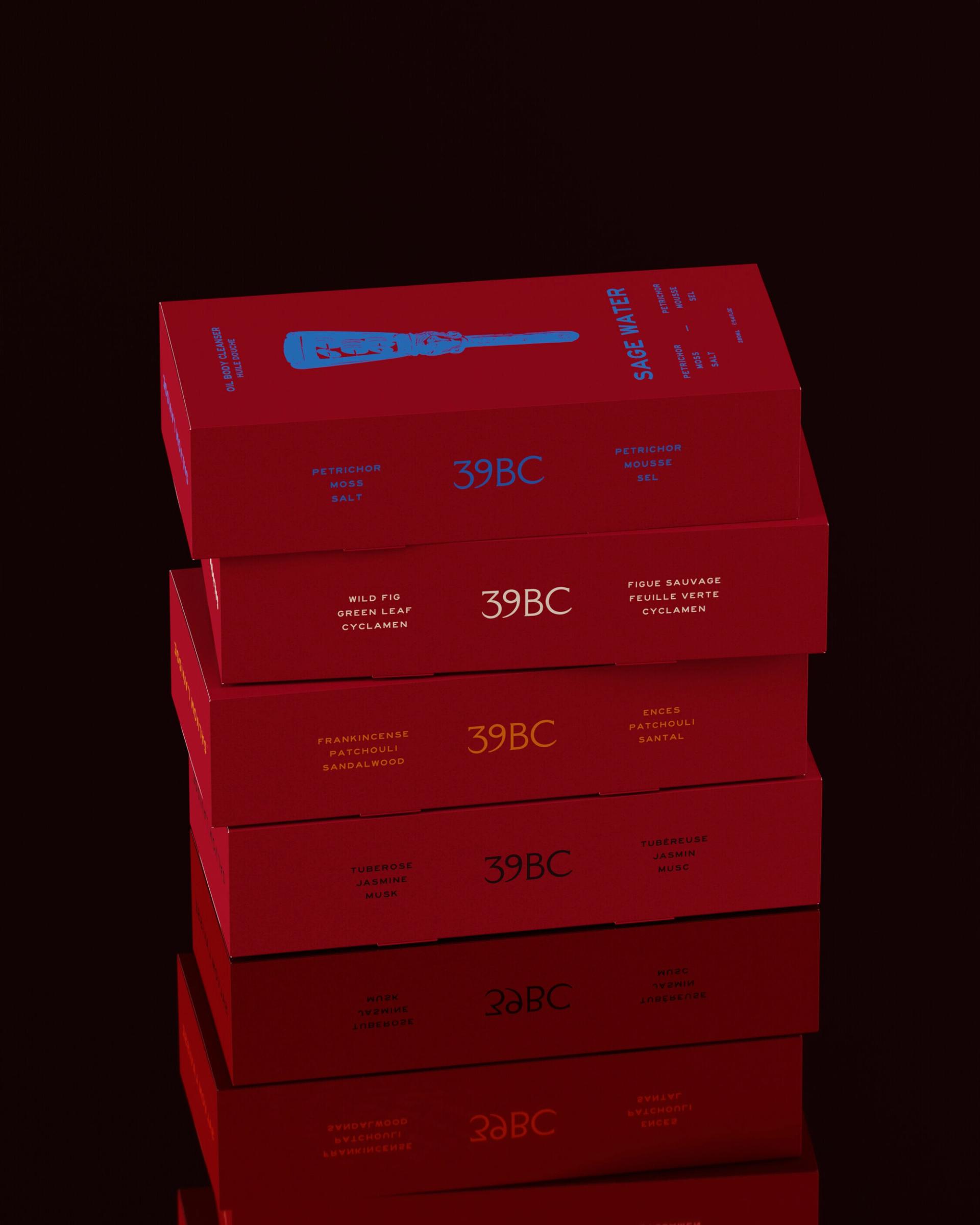

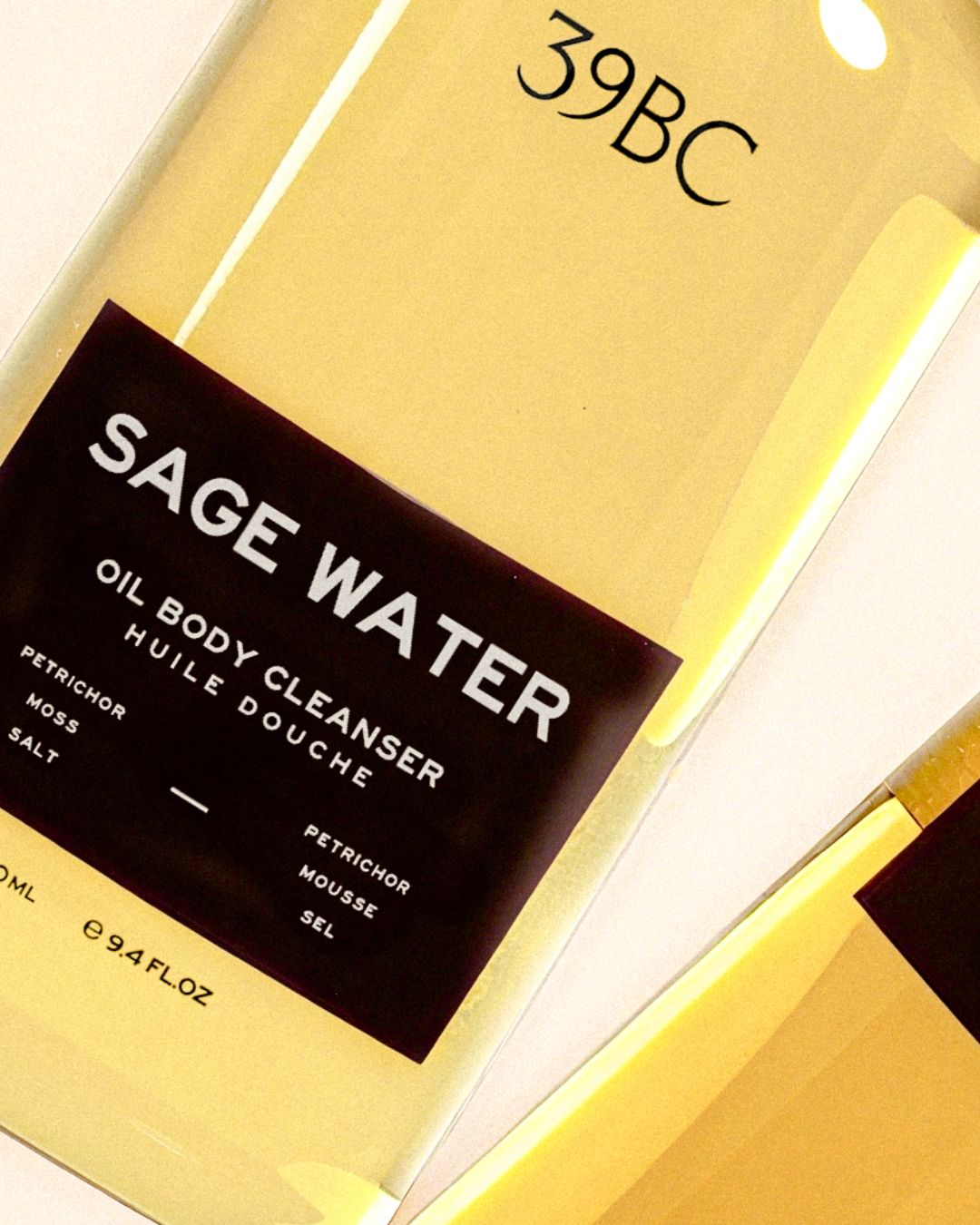

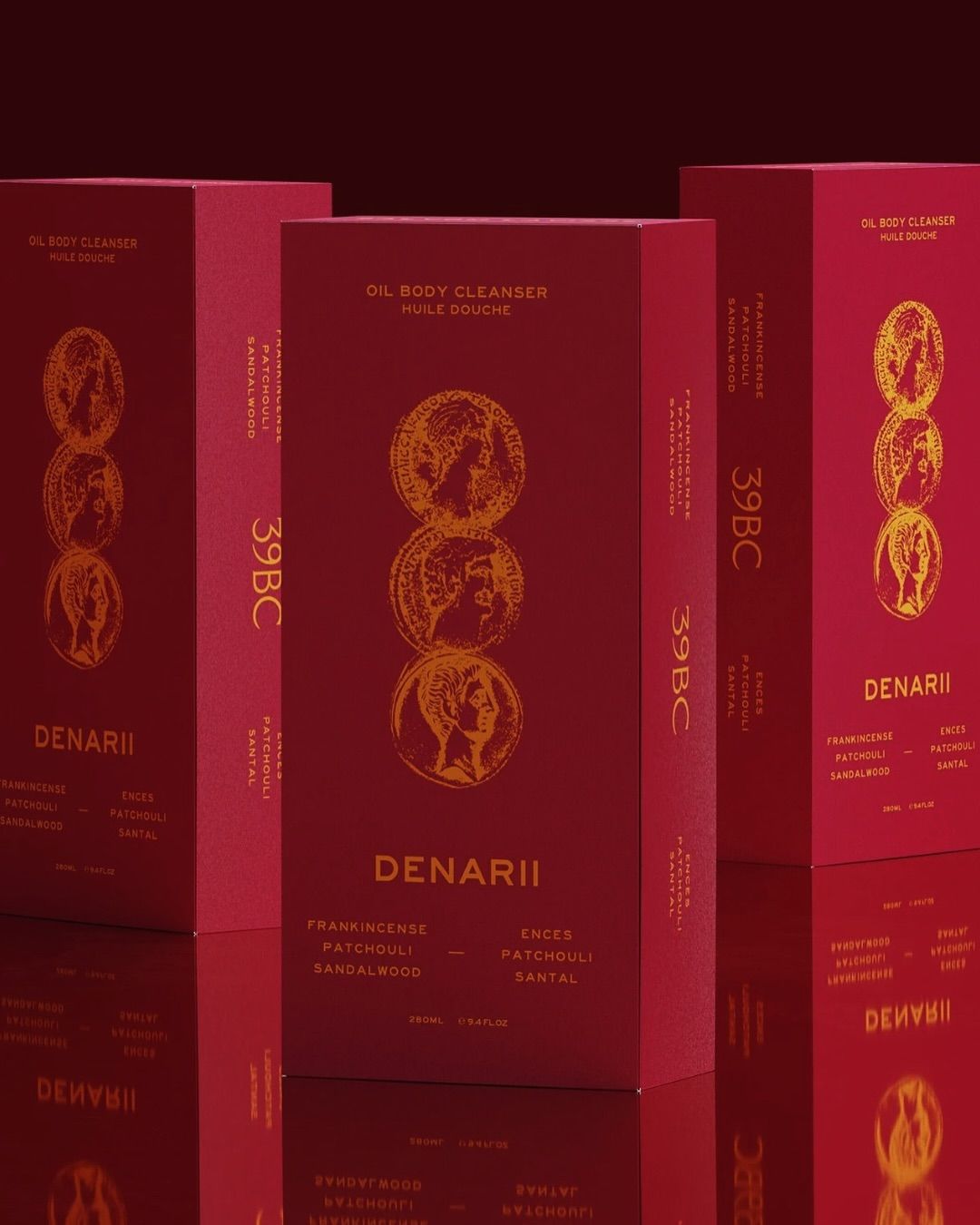

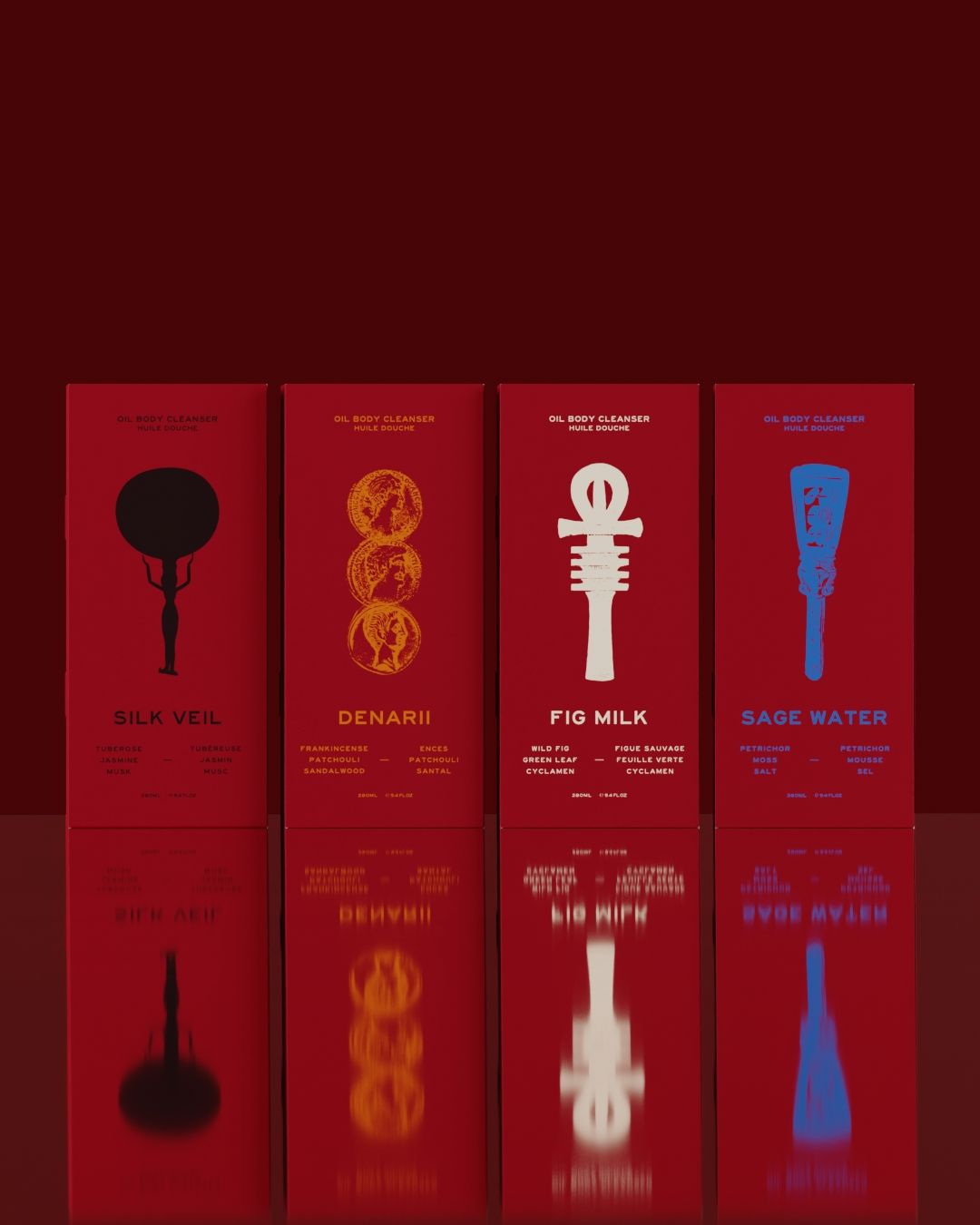

That legacy endures at 39BC. Silk Veil, a fine-fragrance shower oil of neroli, tuberose, jasmine, amber, and musk, carries the intimacy of those private preparations — ritual as presence, fragrance as memory.