It is the first colour the human hand reached for, drawn from iron-rich ochre, pressed into cave walls from Blombos to Altamira. Red came before empire. Before script. It marked presence: I am here. Remember me.

In Cleopatra’s world, red deepened into decadence. Tyrian dye, extracted from the Murex snail, began as blood - a dark, viscous fluid that oxidised in sunlight from crimson to a regal violet. Pliny the Elder described it as “the colour of coagulatus cruor” - clotted blood (Natural History, Book IX, ch. 60).

It was rare. Laborious. Expensive. Tens of thousands of snails crushed for a single garment. Draped on generals, priests, queens - it became law in Rome that only emperors could wear the richest shade. Red was no longer just memory. It was a decree.

But red has always been the colour of bodies - blood, birth, heat, desire. And the colour of power. Roman soldiers marched in red, dyed with madder root - not just to rally morale, but to mask blood loss. Across the field, red meant allegiance. Even when flesh beneath the armour faltered.

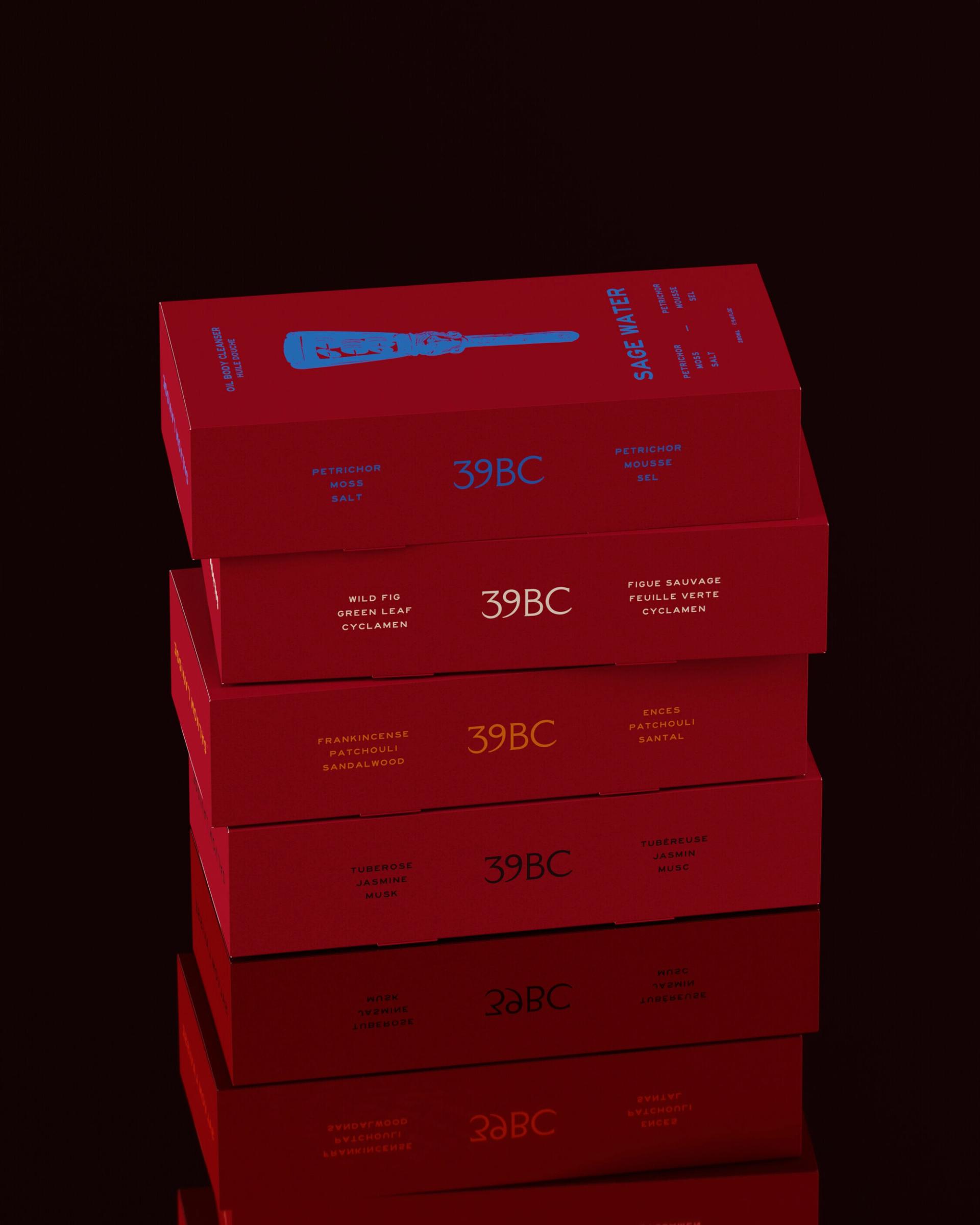

For 39BC, red is not aesthetic. It is archaeological. Emotional. Sensual.

Red leaves its trace on stone, on cloth, on memory.

And isn’t that the point of ritual?

Not just to cleanse, but to remain.