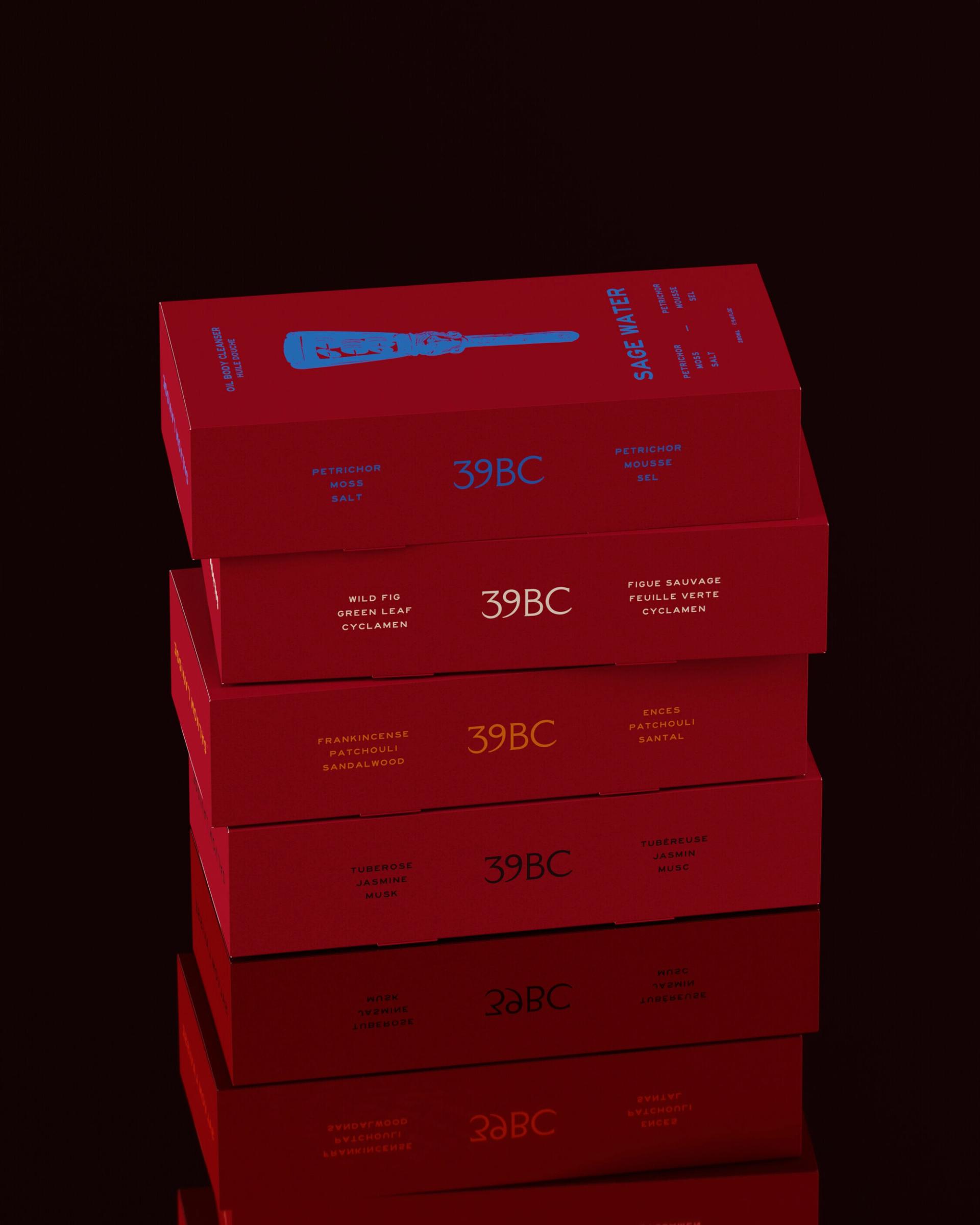

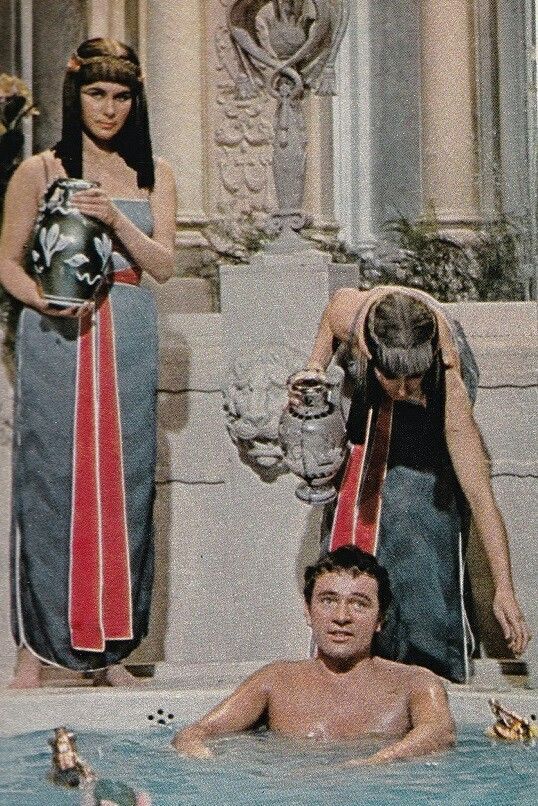

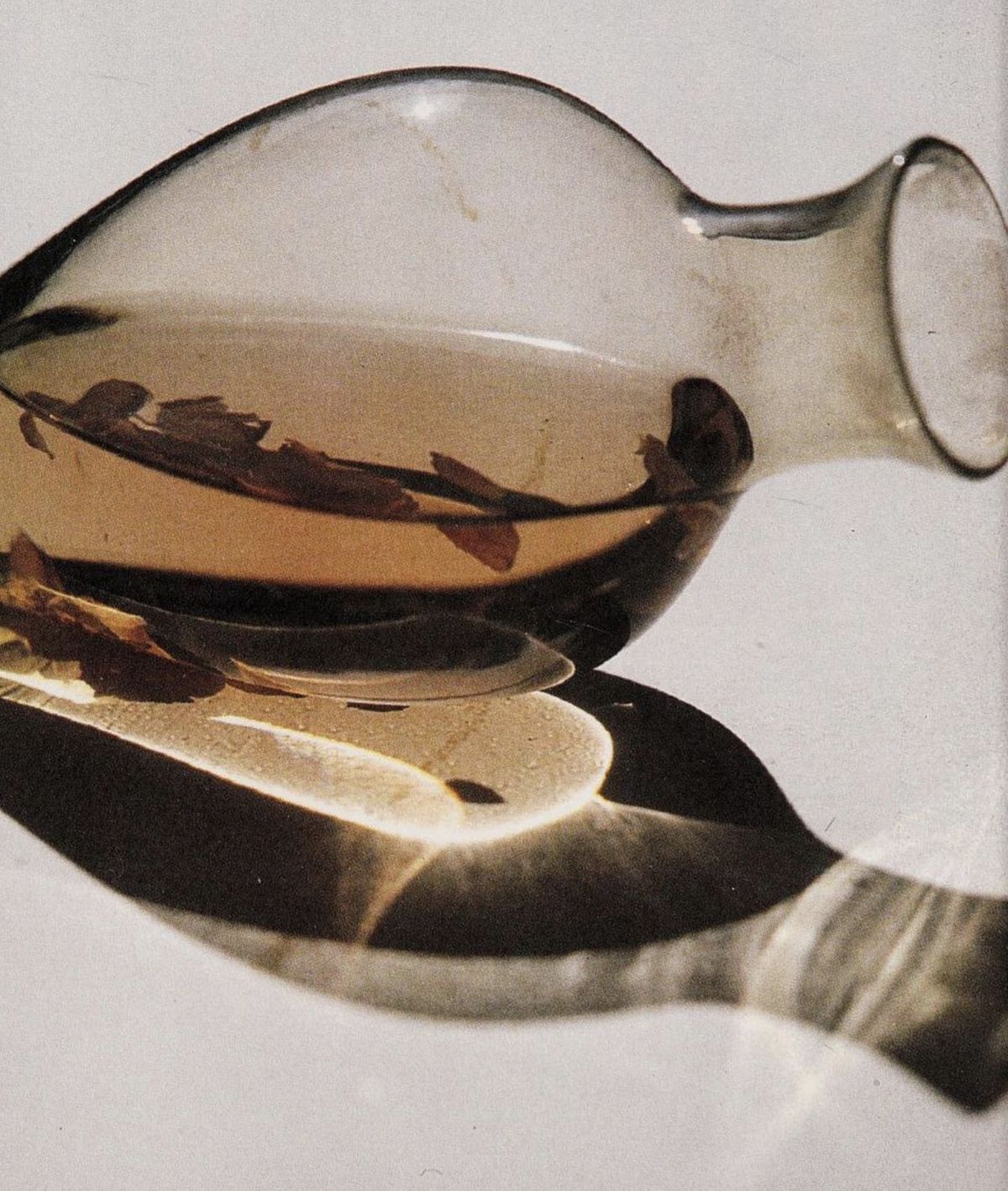

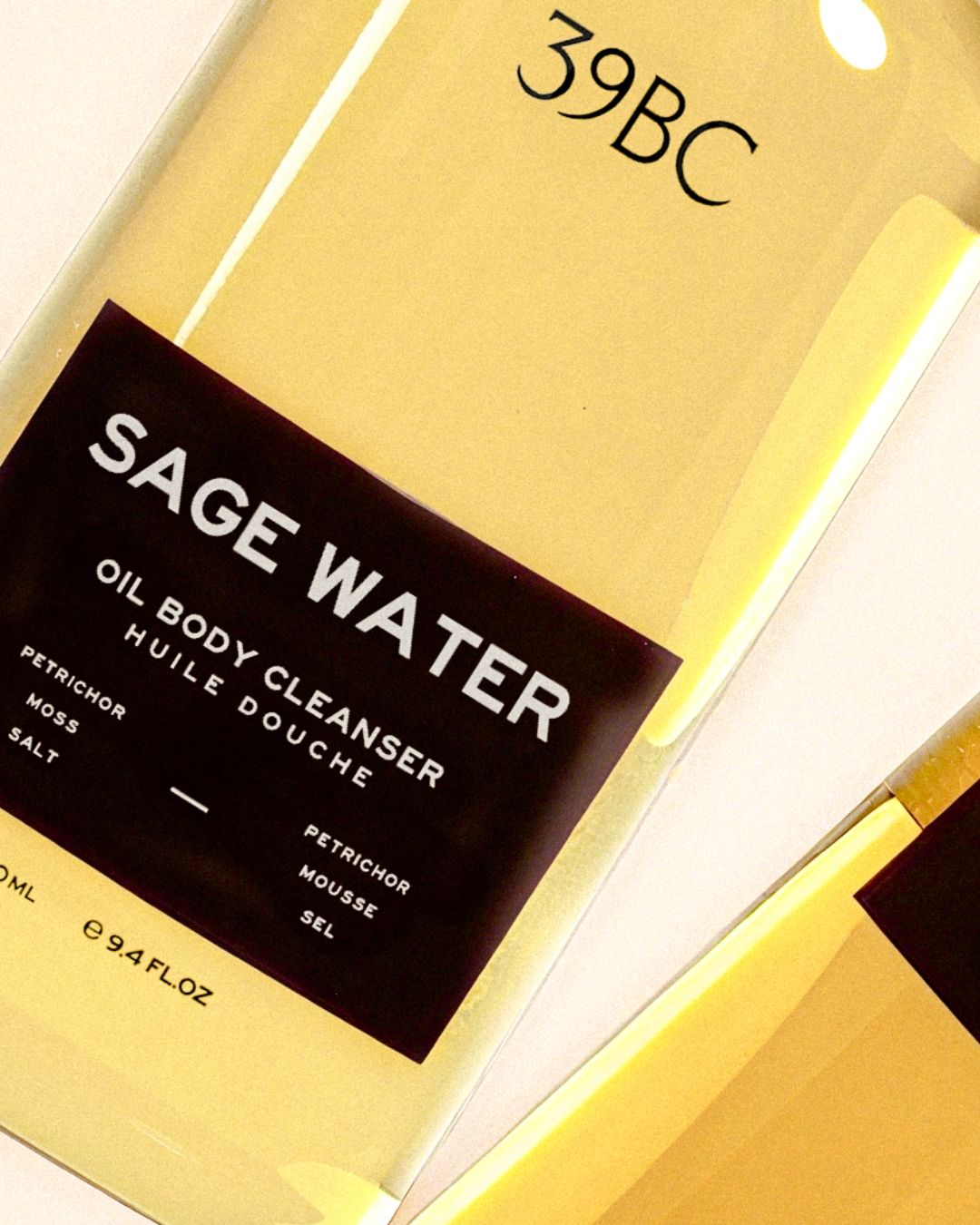

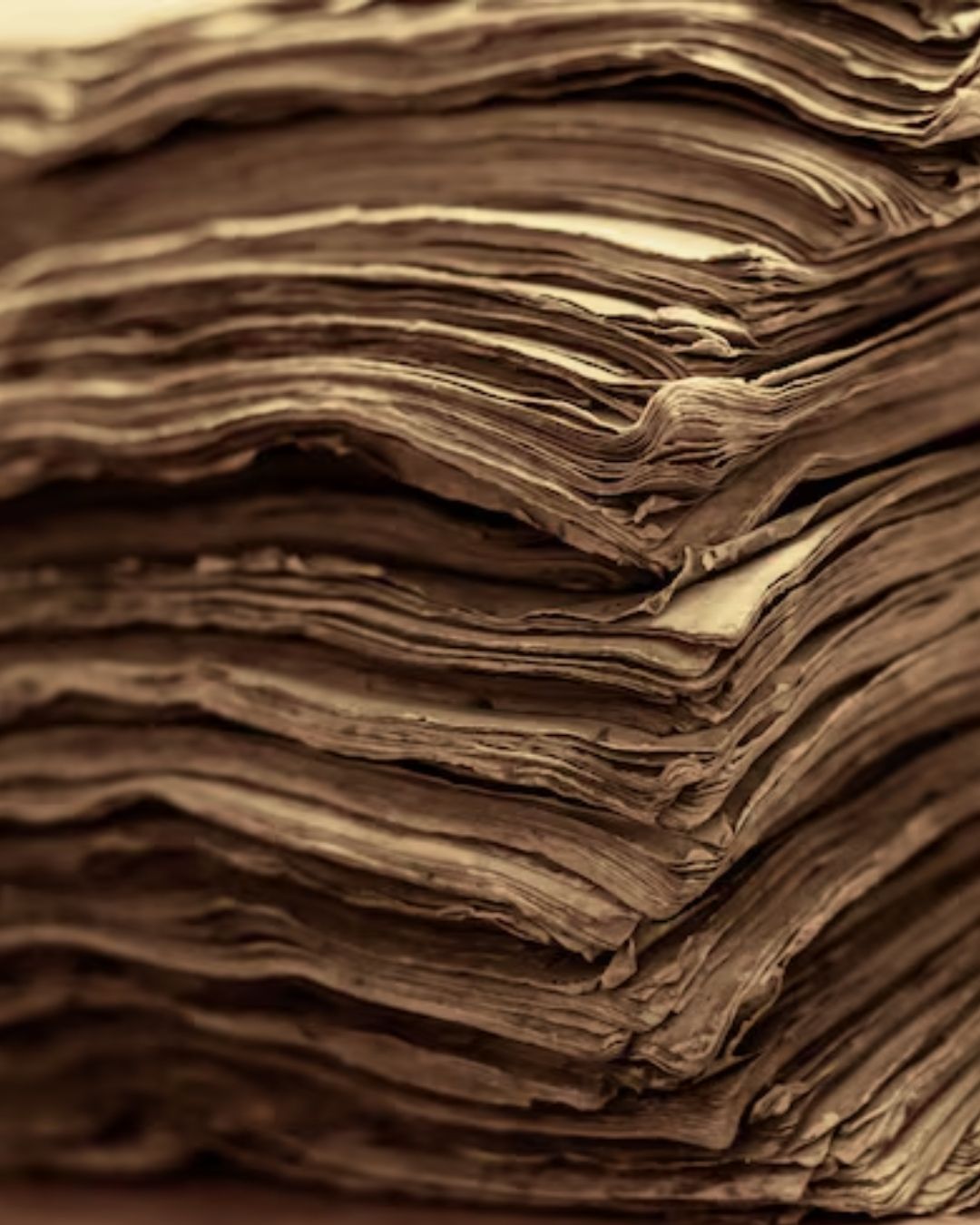

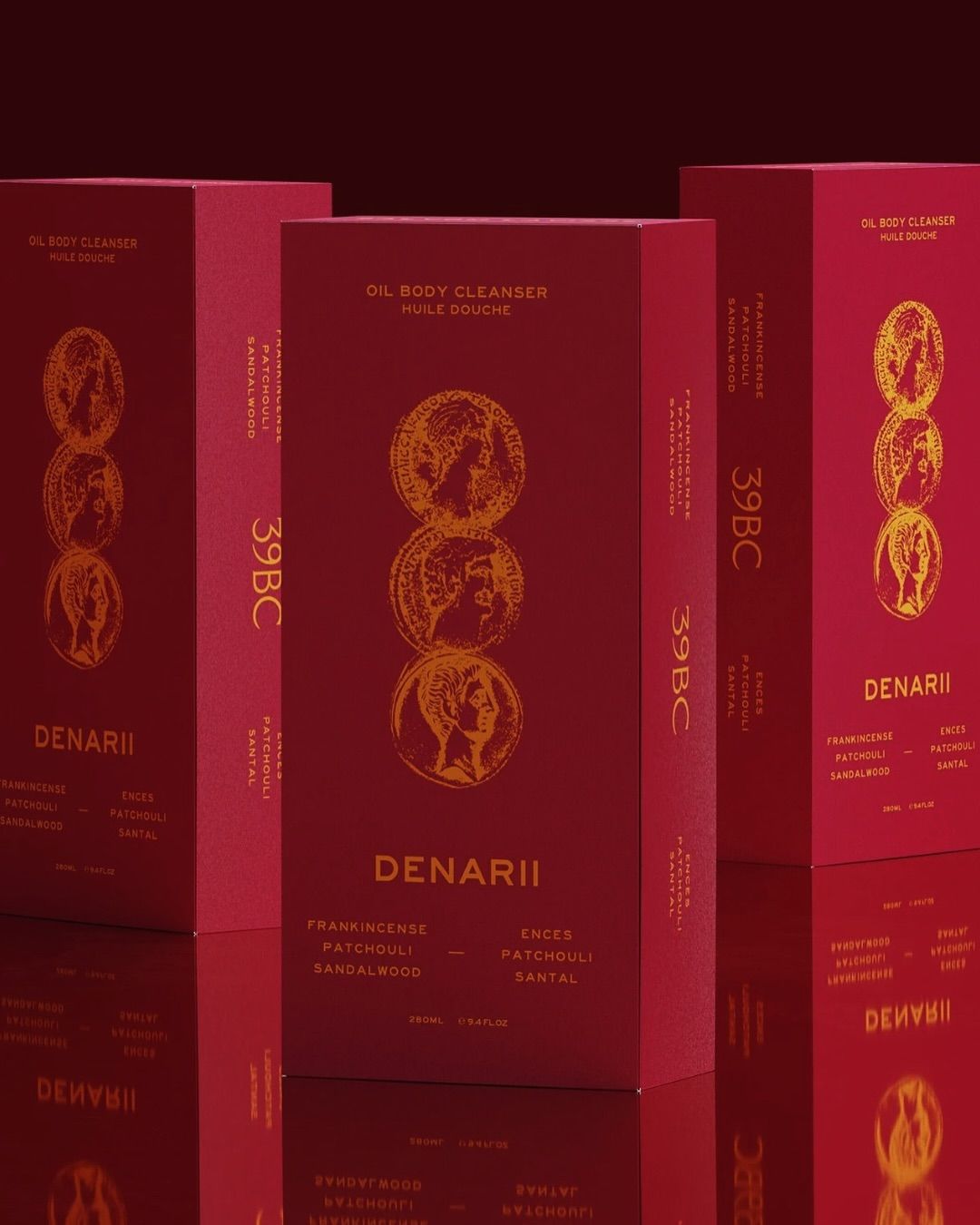

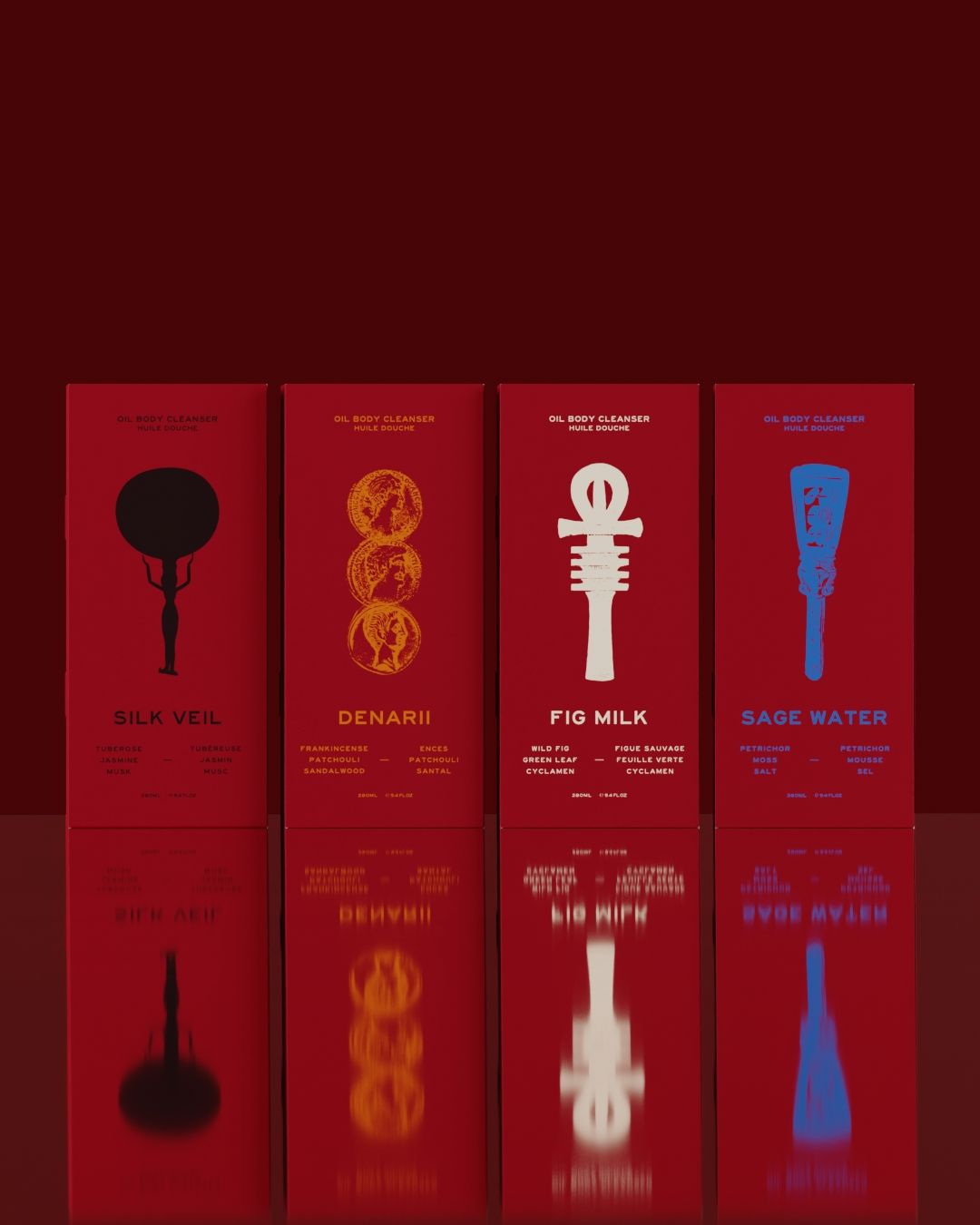

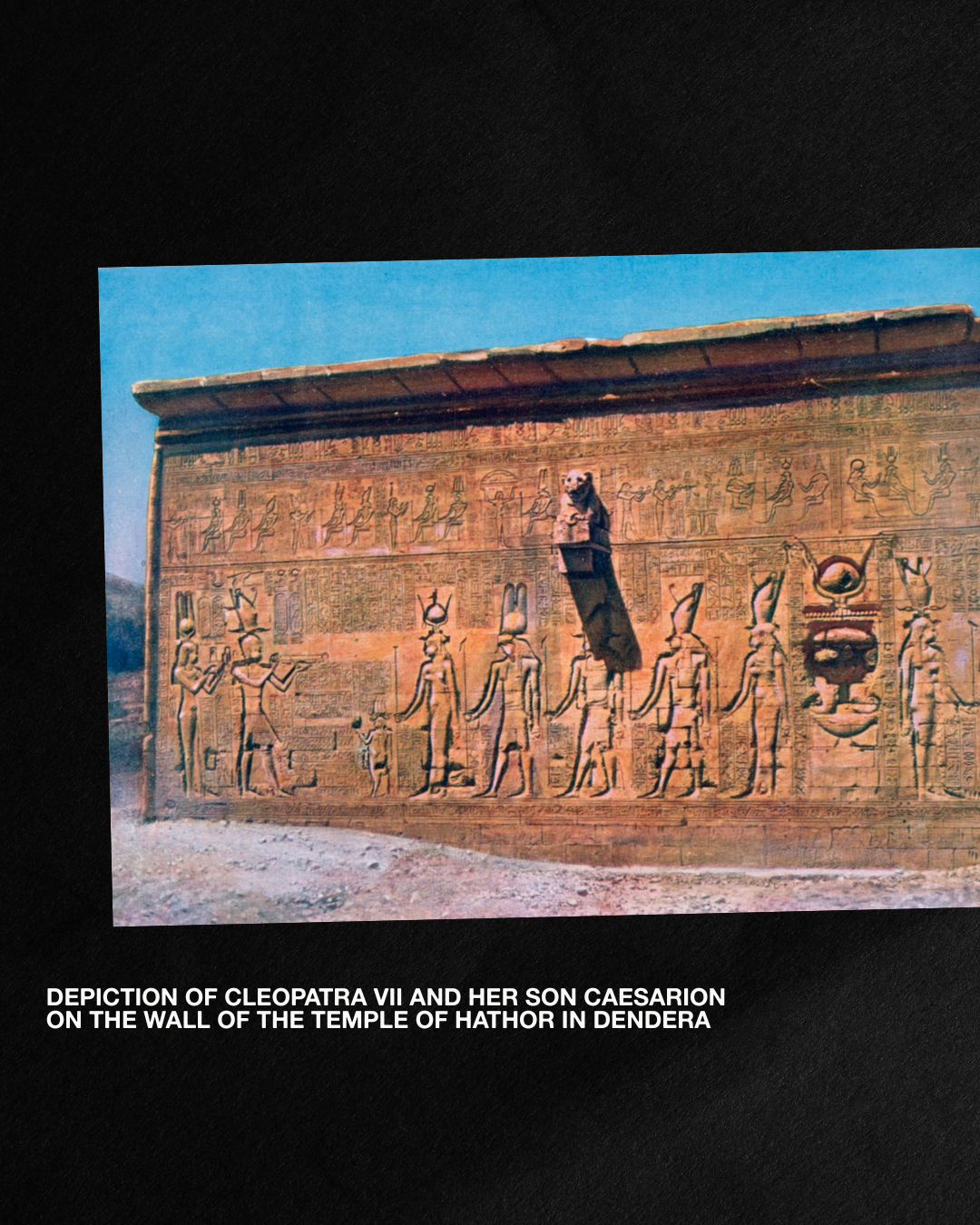

If you’ve bought a bottle of 39BC, it probably came wrapped in this very special tissue paper. Let me tell you about it.

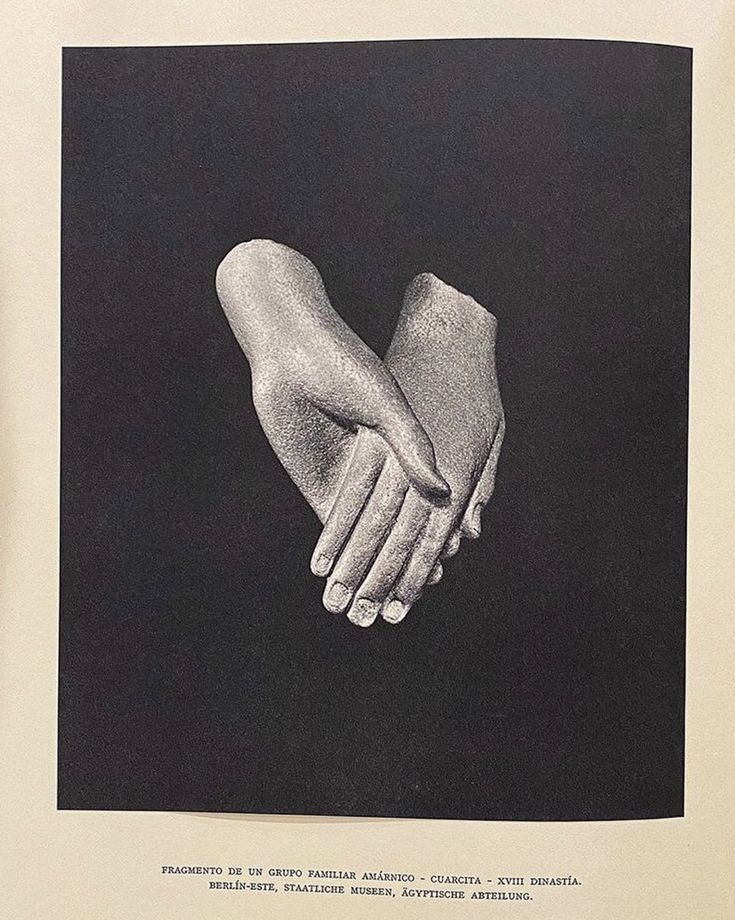

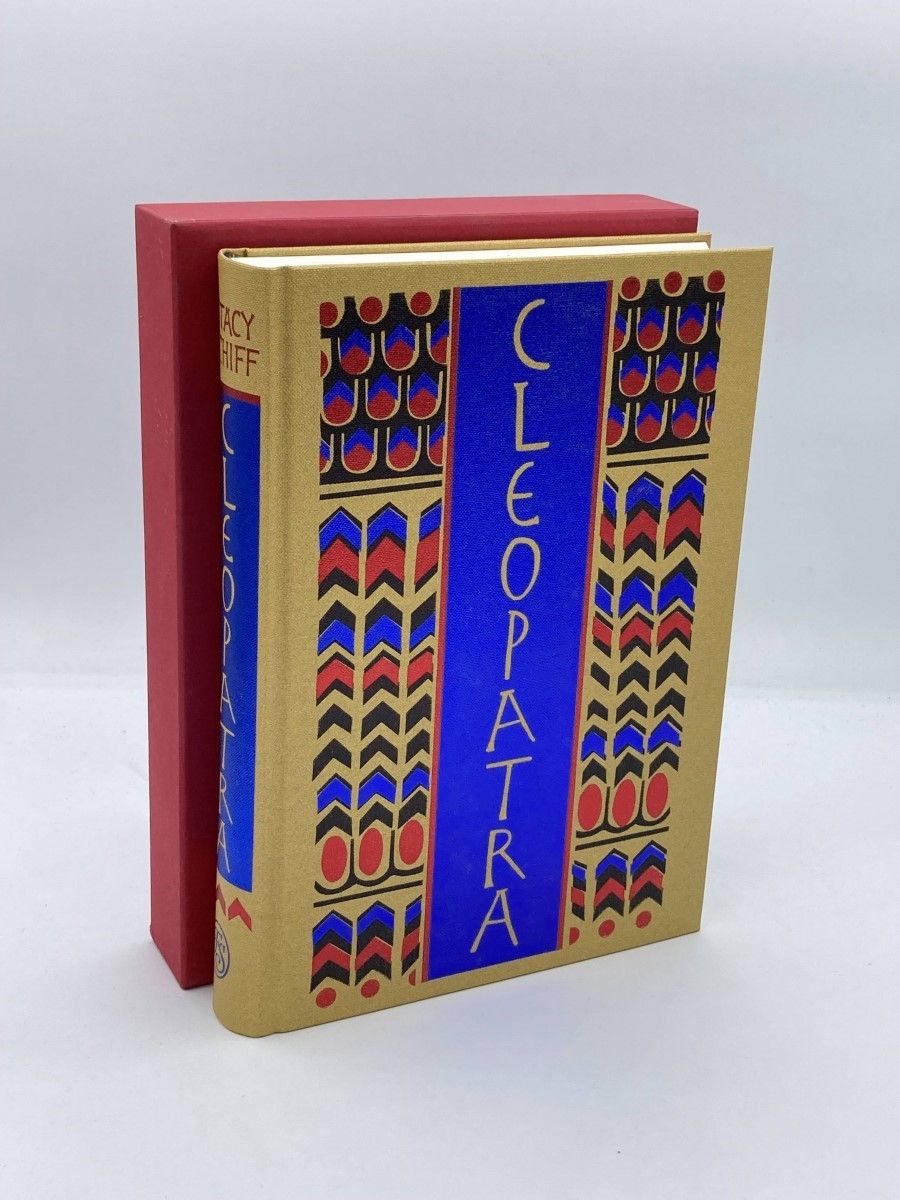

The print comes from a relief at the Temple of Dendera – one of the few surviving images of Cleopatra VII with her son Caesarion. It’s extraordinary because it isn’t just royal propaganda. It’s theology. It’s myth-making. It’s identity. In this scene, Cleopatra is shown as Isis, the great mother. Caesarion – her only child with Julius Caesar (and his only son and heir) – is depicted as Horus, the divine son who inherits both earthly and cosmic power. The Egyptians believed kingship passed not just through blood, but through sacred lineage. So for Cleopatra to present Caesarion as Horus was a declaration to the world: my son is the rightful ruler of Egypt.

Historically, Caesar publicly acknowledged Caesarion as his child in private, even if the Roman Senate refused to accept it. Roman politics could not tolerate the idea of a foreign-born heir. But in Egypt, Caesarion’s identity was never in doubt. He was the last Pharaoh of Egypt – crowned at just three years old, and the final link in a 3,000-year line of divine kings. That’s why this relief matters. It symbolises a mother protecting her dynasty. A child born into myth and danger. And the final moment before Egypt fell into Roman hands.

So when your 39BC bottle arrives wrapped in this tissue paper, you’re touching a tiny fragment of that story – Cleopatra, Caesarion, Isis, Horus, power, lineage, legacy – carried forward into the present, folded carefully around something made with intention.